Te

Kaunihera o Tai Tokerau ki te Raki

AGENDA

Strategy and Policy Committee Meeting

Thursday, 30 July 2020

|

Time:

|

9:30 am

|

|

Location:

|

Council Chamber

Memorial Avenue

Kaikohe

|

Membership:

Cr Rachel

Smith - Chairperson

Cr David Clendon

– Deputy Chairperson

Mayor John

Carter

Deputy Mayor

Ann Court

Cr Dave

Collard

Cr Felicity

Foy

Cr Moko

Tepania

Cr John

Vujcich

Bay of

Islands-Whangaroa Community Board Chairperson Belinda Ward

|

|

Authorising Body

|

Mayor/Council

|

|

Status

|

Standing Committee

|

|

COUNCIL COMMITTEE

|

Title

|

Strategy and Policy Committee

Terms of

Reference

|

|

Approval Date

|

19 December 2019

|

|

Responsible Officer

|

Chief Executive

|

Purpose

The purpose of the Strategy and

Policy Committee (the Committee) is to set direction for the district,

determine specific outcomes that need to be met to deliver on that vision, and

set in place the strategies, policies and work programmes to achieve those

goals.

In determining and shaping the

strategies, policies and work programme of the Council, the Committee takes a

holistic approach to ensure there is strong alignment between the objectives

and work programmes of the strategic outcomes of Council, being:

·

Better data and information

·

Affordable core infrastructure

·

Improved Council capabilities and performance

·

Address affordability

·

Civic leadership and advocacy

·

Empowering communities

The Committee will review the

effectiveness of the following aspects:

·

Trust and confidence in decision-making

by keeping our communities informed and involved in decision-making;

·

Operational performance including

strategy and policy development, monitoring and reporting on significant

projects, including, but not limited to:

o

FN2100

o

District wide strategies (Infrastructure/

Reserves/Climate Change/Transport)

o

District Plan

o

Significant projects (not

infrastructure)

o

Financial Strategy

o

Data Governance

o

Affordability

·

Consultation and engagement including

submissions to external bodies / organisations

To perform his or her role

effectively, each Committee member must develop and maintain

his or her skills and knowledge,

including an understanding of the Committee’s responsibilities, and of

the Council’s business, operations and risks.

Power to

Delegate

The Strategy

and Policy Committee may not delegate any of its responsibilities, duties or

powers.

Membership

The Council will determine the

membership of the Strategy and Policy Committee.

The Strategy and Policy

Committee will comprise of at least seven elected members (one of which

will be the chairperson).

|

Mayor

Carter

|

|

Rachel

Smith – Chairperson

|

|

David

Clendon – Deputy Chairperson

|

|

Moko

Tepania

|

|

Ann

Court

|

|

Felicity

Foy

|

|

Dave

Collard

|

|

John

Vujcich

|

|

|

Non-appointed

councillors may attend meetings with speaking rights, but not voting rights.

Quorum

The quorum at a

meeting of the Strategy and Policy Committee is 5 members.

Frequency of

Meetings

The Strategy and Policy Committee shall meet every 6 weeks,

but may be cancelled if there is no business.

Committees

Responsibilities

The Committees responsibilities

are described below:

Strategy

and Policy Development

·

Oversee the Strategic Planning and

Policy work programme

·

Develop and agree strategy and policy

for consultation / engagement;

·

Recommend to Council strategy and

policy for adoption;

·

Monitor and review strategy and policy.

Service

levels (non regulatory)

·

Recommend service level changes and new

initiatives to the Long Term and Annual Plan processes.

Policies and Bylaws

·

Leading the development and review of Council's policies and

district bylaws when and as directed by Council

·

Recommend to Council new or amended bylaws for adoption

Consultation

and Engagement

·

Conduct any consultation processes

required on issues before the Committee;

·

Act as a community interface (with, as

required, the relevant Community Board(s)) for consultation on policies and as

a forum for engaging effectively;

·

Receive reports from Council’s

Portfolio and Working Parties and monitor engagement;

·

Review as necessary and agree the model

for Portfolios and Working Parties.

Strategic

Relationships

·

Oversee Council’s strategic

relationships, including with Māori, the Crown and foreign investors,

particularly China

·

Oversee, develop and approve engagement opportunities triggered

by the provisions of Mana Whakahono-ā-Rohe under the Resource

Management Act 1991

·

Recommend to Council the adoption of

new Memoranda of Understanding (MOU)

·

Meet annually with local MOU partners

·

Quarterly reviewing operation of all

Memoranda of Understanding

·

Quarterly reviewing Council’s

relationships with iwi, hapū, and post-settlement governance entities in

the Far North District

·

Monitor Sister City relationships

·

Special projects (such as Te Pū o

Te Wheke or water storage projects)

Submissions

and Remits

·

Approve submissions to, and endorse

remits for, external bodies / organisations and on legislation and regulatory

proposals, provided that:

o

If there is insufficient time for the

matter to be determined by the Committee before the submission “close

date” the submission can be agreed by the relevant Portfolio Leaders,

Chair of the Strategy and Policy Committee, Mayor and Chief Executive (all

Councillors must be advised of the submission and provided copies if

requested).

o

If the submission is of a technical and

operational nature, the submission can be approved by the Chief Executive (in

consultation with the relevant Portfolio Leader prior to lodging the

submission).

·

Oversee, develop and approve any

relevant remits triggered by governance or management commencing in January of

each calendar year.

·

Recommend to Council those remits that

meet Council’s legislative, strategic and operational objectives to

enable voting at the LGNZ AGM. All endorsements will take into account

the views of our communities (where possible) and consider the unique

attributes of the district.

Fees

·

Set fees in accordance with legislative

requirements unless the fees are set under a bylaw (in which case the decision

is retained by Council and the committee has the power of recommendation) or

set as part of the Long Term Plan or Annual Plan (in which case the decision

will be considered by the Long Term Plan and Annual Plan and approved by

Council).

District

Plan

·

Review and approve for notification a proposed District Plan, a

proposed change to the District Plan, or a variation to a proposed plan or

proposed plan change (excluding any plan change notified under clause 25(2)(a),

First Schedule of the Resource Management Act 1991);

·

Withdraw a proposed plan or plan change under clause 8D, First

Schedule of the Resource Management Act 1991;

·

Make the following decisions to facilitate the administration of

proposed plan, plan changes, variations, designation and heritage order

processes:

§

To authorise the

resolution of appeals on a proposed plan, plan change or variation unless the

issue is minor and approved by the Portfolio Leader District Plan and the Chair

of the Regulatory committee.

§

To decide whether a

decision of a Requiring Authority or Heritage Protection Authority will be

appealed to the Environment Court by council and authorise the resolution of

any such appeal.

§

To consider and approve

council submissions on a proposed plan, plan changes, and variations.

§ To manage the private plan change process.

§ To accept, adopt or reject private plan change

applications under clause 25 First Schedule Resource Management Act (RMA).

Rules and Procedures

Council’s

Standing Orders and Code of Conduct apply to all the committee’s

meetings.

Annual reporting

The Chair of the Committee will

submit a written report to the Chief Executive on an annual basis. The

review will summarise the activities of the Committee and how it has contributed to the Council’s

governance and strategic objectives. The Chief Executive

will place the report on the next available agenda of the governing body.

STRATEGY AND

POLICY COMMITTEE - MEMBERS REGISTER OF INTERESTS

|

Name

|

Responsibility (i.e.

Chairperson etc)

|

Declaration of

Interests

|

Nature of Potential

Interest

|

Member's Proposed

Management Plan

|

|

Hon John Carter QSO

|

Board Member of the

Local Government Protection Programme

|

Board Member of the

Local Government Protection Program

|

|

|

|

Carter Family Trust

|

|

|

|

|

Rachel Smith (Chair)

|

Friends of Rolands Wood

Charitable Trust

|

Trustee

|

|

|

|

Mid North Family

Support

|

Trustee

|

|

|

|

Property Owner

|

Kerikeri

|

|

|

|

Friends who work at Far

North District Council

|

|

|

|

|

Kerikeri Cruising Club

|

Subscription Member and

Treasurer

|

|

|

|

Rachel Smith

(Partner)

|

Property Owner

|

Kerikeri

|

|

|

|

Friends who work at Far

North District Council

|

|

|

|

|

Kerikeri Cruising Club

|

Subscription Member

|

|

|

|

David Clendon

(Deputy Chair)

|

Chairperson – He

Waka Eke Noa Charitable Trust

|

None

|

|

Declare if any issue

arises

|

|

Member of Vision

Kerikeri

|

None

|

|

Declare if any issue

arises

|

|

Joint owner of family

home in Kerikeri

|

Hall Road, Kerikeri

|

|

|

|

David Clendon

– Partner

|

Resident Shareholder on

Kerikeri Irrigation

|

|

|

|

|

David Collard

|

Snapper Bonanza 2011

Limited

|

45% Shareholder and

Director

|

|

|

|

Trustee of Te Ahu

Charitable Trust

|

Council delegate to

this board

|

|

|

|

Deputy Mayor Ann

Court

|

Waipapa Business

Association

|

Member

|

|

Case by case

|

|

Warren Pattinson

Limited

|

Shareholder

|

Building company. FNDC

is a regulator and enforcer

|

Case by case

|

|

Kerikeri Irrigation

|

Supplies my water

|

|

No

|

|

Top Energy

|

Supplies my power

|

|

No other interest

greater than the publics

|

|

District Licensing

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

Top Energy Consumer

Trust

|

Trustee

|

Crossover in regulatory

functions, consenting economic development and contracts such as street

lighting.

|

Declare interest and

abstain from voting.

|

|

Ann Court Trust

|

Private

|

Private

|

N/A

|

|

Waipapa Rotary

|

Honorary member

|

Potential community

funding submitter

|

Declare interest and

abstain from voting.

|

|

Properties on Onekura

Road, Waipapa

|

Owner Shareholder

|

Any proposed FNDC

Capital works or policy change which may have a direct impact (positive/adverse)

|

Declare interest and

abstain from voting.

|

|

Property on Daroux Dr,

Waipapa

|

Financial interest

|

Any proposed FNDC

Capital works or policy change which may have a direct impact (positive/adverse)

|

Declare interest and abstain

from voting.

|

|

Flowers and gifts

|

Ratepayer 'Thankyou'

|

Bias/

Pre-determination?

|

Declare to Governance

|

|

Coffee and food

|

Ratepayers sometimes

'shout' food and beverage

|

Bias or

pre-determination

|

Case by case

|

|

Staff

|

N/A

|

Suggestion of not being

impartial or pre-determined!

|

Be professional, due

diligence, weigh the evidence. Be thorough, thoughtful, considered impartial

and balanced. Be fair.

|

|

Warren Pattinson

|

My husband is a builder

and may do work for Council staff

|

|

Case by case

|

|

Ann Court - Partner

|

Warren Pattinson

Limited

|

Director

|

Building Company. FNDC

is a regulator

|

Remain at arm’s

length

|

|

Air NZ

|

Shareholder

|

None

|

None

|

|

Warren Pattinson

Limited

|

Builder

|

FNDC is the consent

authority, regulator and enforcer.

|

Apply arm’s

length rules

|

|

Property on Onekura

Road, Waipapa

|

Owner

|

Any proposed FNDC

capital work in the vicinity or rural plan change. Maybe a link to policy

development.

|

Would not submit.

Rest on a case by case basis.

|

|

Felicity Foy

|

Director - Northland

Planning & Development

|

I am the director of a

planning and development consultancy that is based in the Far North and have

two employees.

Property owner of

Commerce Street, Kaitaia

|

|

I will abstain from any

debate and voting on proposed plan change items for the Far North District

Plan.

|

|

|

|

|

I will declare a

conflict of interest with any planning matters that relate to resource

consent processing, and the management of the resource consents planning team.

|

|

|

|

|

I will not enter into

any contracts with Council for over $25,000 per year. I have previously

contracted to Council to process resource consents as consultant planner.

|

|

Flick Trustee Ltd

|

I am the director of

this company that is the company trustee of Flick Family Trust that owns

properties Seaview Road – Cable Bay, and Allen Bell Drive - Kaitaia.

|

|

|

|

Elbury Holdings Limited

|

This company is

directed by my parents Fiona and Kevin King.

|

This company owns

several dairy and beef farms, and also dwellings on these farms. The Farms

and dwellings are located in the Far North at Kaimaumau, Bird Road/Sandhills

Rd, Wireless Road/ Puckey Road/Bell Road, the Awanui Straight and Allen Bell

Drive.

|

|

|

Foy Farms Partnership

|

Owner and partner in

Foy Farms - a farm on Church Road, Kaingaroa

|

|

|

|

Foy Farms Rentals

|

Owner and rental

manager of Foy Farms Rentals for 7 dwellings on Church Road, Kaingaroa and 2

dwellings on Allen Bell Drive, Kaitaia, and 1 property on North Road,

Kaitaia, one title contains a cell phone tower.

|

|

|

|

King Family Trust

|

This trust owns several

titles/properties at Cable Bay, Seaview Rd/State Highway 10 and Ahipara -

Panorama Lane.

|

These trusts own

properties in the Far North.

|

|

|

Previous employment at

FNDC 2007-16

|

I consider the staff

members at FNDC to be my friends

|

|

|

|

Shareholder of Coastline

Plumbing NZ Limited

|

|

|

|

|

Felicity Foy -

Partner

|

Director of Coastline

Plumbing NZ Limited

|

|

|

|

|

Friends with some FNDC

employees

|

|

|

|

|

Moko Tepania

|

Teacher

|

Te Kura Kaupapa

Māori o Kaikohe.

|

Potential Council

funding that will benefit my place of employment.

|

Declare a perceived

conflict

|

|

Chairperson

|

Te Reo o Te Tai Tokerau

Trust.

|

Potential Council

funding for events that this trust runs.

|

Declare a perceived

conflict

|

|

Tribal Member

|

Te Rūnanga o Te

Rarawa

|

As a descendent of Te

Rarawa I could have a perceived conflict of interest in Te Rarawa Council

relations.

|

Declare a perceived

conflict

|

|

Tribal Member

|

Te Rūnanga o

Whaingaroa

|

As a descendent of Te

Rūnanga o Whaingaroa I could have a perceived conflict of interest in Te

Rūnanga o Whaingaroa Council relations.

|

Declare a perceived

conflict

|

|

Tribal Member

|

Kahukuraariki Trust

Board

|

As a descendent of

Kahukuraariki Trust Board I could have a perceived conflict of interest in

Kahukuraariki Trust Board Council relations.

|

Declare a perceived

conflict

|

|

Tribal Member

|

Te Rūnanga

ā-Iwi o Ngāpuhi

|

As a descendent of Te

Rūnanga ā-Iwi o Ngāpuhi I could have a perceived conflict of

interest in Te Rūnanga ā-Iwi o Ngāpuhi Council relations.

|

Declare a perceived

conflict

|

|

John Vujcich

|

Board Member

|

Pioneer Village

|

Matters relating to

funding and assets

|

Declare interest and

abstain

|

|

Director

|

Waitukupata Forest Ltd

|

Potential for council

activity to directly affect its assets

|

Declare interest and

abstain

|

|

Director

|

Rural Service Solutions

Ltd

|

Matters where council

regulatory function impact of company services

|

Declare interest and

abstain

|

|

Director

|

Kaikohe (Rau Marama) Community

Trust

|

Potential funder

|

Declare interest and

abstain

|

|

Partner

|

MJ & EMJ Vujcich

|

Matters where council

regulatory function impacts on partnership owned assets

|

Declare interest and

abstain

|

|

Member

|

Kaikohe Rotary Club

|

Potential funder, or

impact on Rotary projects

|

Declare interest and

abstain

|

|

Member

|

New Zealand Institute

of Directors

|

Potential provider of

training to Council

|

Declare a Conflict of

Interest

|

|

Member

|

Institute of IT

Professionals

|

Unlikely, but possible

provider of services to Council

|

Declare a Conflict of

Interest

|

|

Member

|

Kaikohe Business

Association

|

Possible funding

provider

|

Declare a Conflict of

Interest

|

2 Apologies

and Declarations of Interest

Members need to

stand aside from decision-making when a conflict arises between their role as a

Member of the Committee and any private or other external interest they might

have. This note is provided as a reminder to Members to review the matters on

the agenda and assess and identify where they may have a pecuniary or other

conflict of interest, or where there may be a perception of a conflict of

interest.

If a Member

feels they do have a conflict of interest, they should publicly declare that at

the start of the meeting or of the relevant item of business and refrain from

participating in the discussion or voting on that item. If a Member thinks they

may have a conflict of interest, they can seek advice from the Chief Executive

Officer or the Team Leader Democracy Support (preferably before the meeting).

It is noted

that while members can seek advice the final decision as to whether a conflict

exists rests with the member.

3 Deputation

No requests for deputations were received at the time of the

Agenda going to print.

4 Reports

4.1 Joint

Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee

File

Number: A2905655

Author: Roger

Ackers, Manager - Strategy Development

Authoriser: Janice

Smith, Chief Financial Officer

Purpose of the Report

To seek approval from the

Strategy and Policy Committee for the establishment of a Joint Climate Change Adaptation

Governance Committee that is tasked with overseeing the development and

implementation of a Northland region wide climate change adaptation strategy.

To seek approval for the

nomination of Councillor Clendon as the Far North District Council elected

member representative on the proposed Joint Climate Change Committee.

To seek approval to ask

Te Kahu O Taonui to nominate the Far North District Councils tangata whenua

representative on the proposed Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance

Committee.

To see approval for the

development of policy for the remuneration of non-elected members to committees

of Council.

Executive

Summary

· The Climate Adaptation Te Taitokerau Group, a working group of

administration representatives from the four Councils located in the Northland

region, proposed the establishment of a joint standing Committee to the Mayoral

Forum on 10 February 2020 by submitting a draft terms of reference paper

(attachment 1) to the Forum.

· The Mayoral Forum requested further consultation with Māori

advisory groups within each Council to get feedback on the draft terms of

reference for the proposed joint standing committee.

· This paper responds to the request from the Mayoral Forum and the

draft terms of reference for a proposed Joint Climate Change Adaptation

Governance Committee by recommending that the Strategy and Policy Committee;

o Approve the draft Terms of Reference for the proposed Joint Climate

Change Adaptation Governance Committee and

o approve the appointment of Councillor Clendon to the proposed Joint

Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee and that

o Te Kahu O Taonui be asked to nominate the Far North District Council

tangata whenua representative on the proposed Joint Climate Adaptation

Governance Committee and

o approve the development of a policy for the remuneration of

non-elected members to committees of Council.

|

Recommendation

That the Strategy and Policy Committee:

a) approve the

forming of a Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee one tangata

whenua representative from each of the four Councils that are contained in

the Northland Region, these being Northland Regional Council, Whangarei

District Council, Kaipara District Council and Far North District Council and

that;

b) approve that

Councillor Clendon, as the climate change portfolio holder, be appointed as

the Far North District Council elected member representative on the proposed

Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee and that;

c) approve that

Te Kahu O Taonui be asked to nominate the Far North District Council tangata

whenua representative on the proposed Joint Climate Change Adaptation

Governance Committee and that;

d) approve the

development of a policy for the remuneration of non-elected members to

committees of Council.

|

1) Background

· In

mid-2018 representatives of the administration from Kaipara District Council

(KDC), Whangarei District Council (WDC), Northland Regional Council (NRC) and

Far North District Council (FNDC) concluded that a regional wide consistent and

collaborative approach across the four councils was the preferred way forward

for adapting to the impacts of climate change across the Northland Region

· The

first meeting of representatives from the administration of the four Northland

Councils plus representatives from the administration of the Northland

Transport Alliance (NTA) was held in Whangārei on 23 July 2018. At this

meeting it was agreed that a climate change working group be formed with the

intent of collaborating on issues and approaches to responding to climate

change

· It

was also agreed among attendees at the 23 July 2018 meeting that, to legitimise

and give a mandate to a cross council climate change adaptation working group,

that the endorsement by the Northland Chief Executive Officer and Mayoral

Forums was required

· A

draft Terms of Reference for a Northland wide Climate Change Working Group

(CCWG) was submitted to the Chief Executive Officers Forum on 20 August

2018. The Chief Executive Officers Forum endorsed the Terms of Reference

and appointed the Chief Executive Officer from KDC as the project

sponsor. The membership of CCWG includes staff representatives from FNDC,

NRC, KDC, WDC, NTA and the Four Waters Advisory Group

· The

purpose of the CCWG as written in its Terms of Reference is ‘to develop a

regional collaborative approach to climate change adaptation planning for local

government in Northland. This will include a draft climate change strategy for

Northland and an associated work programme that identifies and addresses

priority issues at both a regional and district level’

· The

CCWG has no delegated authority with recommendations of the group requiring

approval by the relevant council(s) prior to the implementation or adoption or

any strategy, plan or governance document like a term of reference

· Since

its inception the CCWG has been working towards the development of a regional

wide climate change adaptation strategy. This has drawn heavily on the

advice and direction provided by the Ministry for the Environment and case

studies from across New Zealand. A consistent message that has come from

the work and analysis undertaken by the CCWG has concluded the success of climate

change adaptation initiatives relies heavily on having clear governance and

oversight groups in place

· A

paper (attachment one) was submitted to the 10 February 2020 Mayoral Forum

proposing the formation of a joint standing committee consisting of elected

member representatives from FNDC, KDC, WDC and NRC and representatives from iwi

/ hapū as ‘nominated by each council from within their

jurisdiction’. This paper also contained a daft Terms of Reference

for the proposed joint standing committee

· Feedback

from the Mayoral Forum on the paper was ‘that while the concept was

supported there needed to be more consultation with Māori advisory groups

from each council before moving forward’

· The

CCWG intends to take the decision from each of the four Northland Councils on

the proposed joint standing committee to the CEO Forum on 10 August 2020

· On

the endorsement of a Joint Climate Change Adaptation Committee by the Chief

Executive Forum each Council will be required to adopt the establishment of the

Joint Standing Committee as per the requirements of the Local Government Act

(clause 30(1)(b) of Schedule 7 to the Local Government Act 2002).

· The

CCWG has undertaken a renaming exercise in recent months. This group is

now referred to as the Climate Adaptation Te Taitokerau (CATT) Group

· On

7 May 2020 Council adopted a Climate Change Roadmap for the Far North District

Council. The Roadmap included implementation initiatives and the

execution of programmes of work that are being proposed by the CATT Group

· Te

Kahu o Taonui is a collective of Taitokerau iwi chairs from Te Aupouri,

Ngāti Kuri, Te Rarawa, Ngāti Kahu, Ngāi Takoto, Ngāpuhi,

Kahukuraariki, Whangaroa, Ngāti Wai, Ngāti Whātua ki Kaipara and

Te Roroa

2) Discussion

and Options

DISCUSSION

· Councillor

Clendon holds the portfolio for Climate Change for the Far

North District Council, as previously approved by full Council. His appointment

to the proposed joint standing committee aligns with this portfolio

· NRC,

KDC and WDC all have forums with iwi and hapū that have been involved in

the work being undertaken by the CCWG, including the development of the

attached draft terms of reference. FNDC has no such forum where it can

discuss the concept of a joint standing committee or seek an iwi/hapū representative

on such a committee.

· Council

does, however, participate in the Iwi Local Government Chief Executives Forum

and is a signatory to the Mayoral Forum/Iwi Chairs Memorandum of Understanding,

Whanaungatanga Ki Taurangi. While council also has a number of other Memorandum

of Understanding with iwi and/or hapū, the Whanaungatanga ki Taurangi is

the only district wide relationship mechanism.

· The

Far North District Council currently has no specific policy that determines the

remuneration of the non-elected members who are appointed to committees of

Council. Northland Regional Council has such a policy.

OPTIONS

Establishment of a

Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee

Option One (preferred

option): The Strategy and Policy Committee approves the draft Terms of

Reference for the Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee as

contained in attachment one to this report.

Under this option the

Strategy and Policy Committee approves the proposed Terms of Reference

(contained in attachment one). If this option is approved Council can

then consider how it will appoint the Far North District Council elected member

representative and the tangata whenua representative on the proposed Joint

Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee. Administration recommends

this option.

Option Two: The

Strategy and Policy Committee does not approve of a Joint Climate Change

Adaptation Governance Committee

Under this option the

Strategy and Policy Committee does not approve the establishment of the proposed

Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee. This decision will

in effect cease the Far North District Council’s involvement in the CATT

Group. Under this option the Far North District Council will develop and

implement its own climate change adaptation strategies and plans. This

option would allow the Far North District Council to develop its response to

climate change at its own pace. However choosing this option has the

following disadvantages;

o The

Far North District Council is likely to experience significant reputational

risk, locally, regionally and nationally as the only Council not to sign up to

a joint governance model for climate change in Northland

o The

Far North District Council would not be able to benefit from drawing on the

skills of other originations, particularly the Northland Regional Council who

do the climate change related data modelling for Northland

o The

Far North District Council may not be able to secure national funding for

climate change response initiatives due to its non-participation in any

regional initiatives on climate change.

Option Three:

The Strategy and Policy Committee requests that the draft Terms of Reference

for the Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee be modified

Under this option the

Strategy and Policy Committee reviews and requests modification to the proposed

Terms of Reference (contained in attachment one) that ensures that the intent

of this document is aligned with the Far North District Councils goals and

objectives. Under this option, on direction from the Strategy and Policy

Committee, administration will draft up changes to the Terms of Reference that

will be submitted to the CATT group for further consideration before an agreed

Terms of Reference is submitted to the Northland Chief Executive Officers

Forum.

Appointment of Far

North District Elected Member representative on the proposed Joint Climate

Change Adaptation Governance Committee

Administration recommends

that Council appoints the climate change portfolio holder, Councillor Clendon,

as the Far North District Council nominated elected member representative on

the proposed Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee.

Appointment of the Far

North District tangata whenua representative to the proposed Joint Climate

Change Adaptation Governance Committee

Option One (preferred

option): The Far North District Council tangata whenua representative on the

proposed Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee is appointed by

Te Kahu O Taonui

Using the Whanaungatanga

ki Taurangi agreement, Council will approach Te Kahu o Taonui with a view that

Te Kahu o Taonui appoint a member as the Far North tangata whenua

representative on to the Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee

as the Far North District representative.

This approach would see

Council give weight to the relationship agreement it signed at Waitangi in

February 2019. It also provides a District wide perspective from iwi/hapū

due to the nature of Te Kahu o Taonui being representative of the districts

iwi.

Engaging with Te Kahu o

Taonui would also develop trust and build stronger relationships between the

governance of iwi and Council which would have wider beneficial outcomes for

Council and iwi.

Under this option the Far

North District Council will need to adopt a policy for remuneration of

non-elected members who are appointed to committees of Council.

Option Two: The

Far North District Council tangata whenua representative on the proposed the

Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee is appointed via a public

expression of interest process

Council will advertise in

the public notices and undertake a tender process to appoint a tangata whenua

non-elected member on to the Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance Committee

as the Far North District representative. This process would see council on its

own, without discussion or endorsement by iwi/hapū, appoint a tangata

whenua representative to the proposed joint committee.

Option Three: The

Council makes a direct appointment of the Far North District Council tangata

whenua representative on the proposed Joint Climate Change Adaptation

Governance Committee

This option would see

Council alone deciding as to who would be best qualified to represent the views

of Māori in the Far North District on the proposed Joint Climate Change

Adaptation Governance Committee.

Reason

for the recommendation

· Administration

recommends that the Strategy and Policy Committee approves the proposed Terms

of Reference (attachment one) to demonstrate the Far North District

Council’s commitment to a Northland wide approach to climate change

adaptation. This option has the following advantages:

o This

will ensure a regionally consistent approach to climate change adaptation and

allow for greater synergies with policies and strategies, and Resource

Management Act planning

o A

regional approach will enable Northland Councils to lobby for central

government financial contributions for projects given the collaborative nature

of the arrangement

· Administration

recommends the appointment of Councillor Clendon as the elected member

representative on the proposed Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance

Committee as it aligns and shows commitment to the portfolio assignment that

Council has made

· Administration

recommends that the appointment of a Far North District Council tangata whenua

representative to the proposed Joint Climate Change Adaptation Governance

Committee is best determined and endorsed by Te Kahu O Taonui as this respects

the mana of this group and demonstrates a commitment to and respect for the

relationship between the Far North District Council and Te Kahu O Taonui.

This option has the following advantages:

o Engaging

Te Kahu o Taonui responds to Whanaungatanga Ki Taurangi and is an appropriate

response by the Far North District Council.

o It

provides for the Far North District Councils obligations as prescribed in the

Local Government Act 2002, section 81 by providing Māori input into the

decision-making processes of council.

· Administration

recommends the development and adoption of a policy for the remuneration of

non-elected members to committees of Council.

3) Financial

Implications and Budgetary Provision

There are no direct

financial implications associated with the recommendation made in this

paper. The development of a policy for the remuneration of non-elected

members to committees of Council will articulate the quantum and form of

remuneration of those appointed to a committee. These details will be contained

in a future paper to the committee.

Attachments

1. 10 February 2020

Mayoral Forum - Joint Council Climate Change Adaptation Committee Proposal and

draft terms of reference - A2906404 ⇩

Compliance schedule:

Full consideration has been given to the provisions of the

Local Government Act 2002 S77 in relation to decision making, in particular:

1. A

Local authority must, in the course of the decision-making process,

a) Seek

to identify all reasonably practicable options for the achievement of the

objective of a decision; and

b) Assess

the options in terms of their advantages and disadvantages; and

c) If

any of the options identified under paragraph (a) involves a significant

decision in relation to land or a body of water, take into account the

relationship of Māori and their culture and traditions with their

ancestral land, water sites, waahi tapu, valued flora and fauna and other

taonga.

2. This

section is subject to Section 79 - Compliance with procedures in relation to

decisions.

|

Compliance

requirement

|

Staff

assessment

|

|

State the level of significance

(high or low) of the issue or proposal as determined by the Council’s

Significance and Engagement Policy

|

The recommendations made in this

paper do not exceed any of the significance thresholds contained in the

Council’s Significance and Engagement Policy.

|

|

State the relevant Council

policies (external or internal), legislation, and/or community outcomes (as

stated in the LTP) that relate to this decision.

|

Clause 30(1)(b) of Schedule 7 to

the Local Government Act 2002 gives the power to a local authority to appoint

a joint committee with another local authority or other public body as per

the recommendations in this report.

The following Council policy is

relevant, but not directly related, to the recommendation in this report:

· Appointment

and Remuneration of Directors for Council Organisations.

|

|

State whether this issue or

proposal has a District wide relevance and, if not, the ways in which the

appropriate Community Board’s views have been sought.

|

The recommendation in this report

has district wide relevance.

|

|

State the possible implications for Māori

and how Māori have been provided with an opportunity to contribute to

decision making if this decision is significant and relates to land and/or

any body of water.

|

Māori will be

disproportional impacted by the impacts of climate change. In providing for a

standing committee to develop adaption strategies which is a co-governance

arrangement of iwi and councils will provide Māori direct input into

council decisions around Climate Change Adaption.

|

|

Identify persons likely to be

affected by or have an interest in the matter, and how you have given consideration

to their views or preferences (for example – youth, the aged and those

with disabilities.

|

There are no specific persons

that will be affected by or have an interest in the recommendation in this

report that required special consideration of their views or preferences.

|

|

State the financial implications

and where budgetary provisions have been made to support this decision.

|

There are no direct financial

implications associated with the recommendation made in this paper.

|

|

Chief Financial Officer review.

|

The Chief Financial Officer has

reviewed this report.

|

|

Strategy and Policy Committee Meeting Agenda

|

30 July 2020

|

Joint climate change adaptation committee

Terms of Reference

10 February 2020

Background

Climate change poses significant risks to the

environment and people of Te Taitokerau - local government has responsibilities

in reducing the impact of climate change (adaptation). It is essential that

councils, communities and iwi / hapū work collaboratively to ensure an

effective, efficient and equitable response to the impacts of climate change.

Work on adaptation has already started between council staff with the formation

of a joint Te Taitokerau Councils Climate Change Adaption Group and the

development of a Climate Change Adaptation Strategy for Taitokerau. The

formation of a joint standing committee of the Far North, Kaipara and Whangarei

district councils and Northland Regional Council elected council members and

iwi / hapū is fundamental to ensuring these outcomes are achieved in a

coordinated and collaborative way across Te Taitokerau.

Role and Responsibilities

1) Provide direction and oversight of

the development and implementation of climate change adaptation activities by

local government in Te Taitokerau

2) Receive advice and provide direction

and support to the Te Taitokerau Councils Climate Change

Adaption Group

3) Make recommendations to member

councils to ensure a consistent regional approach is adopted to climate change

adaptation activities

4) Act collectively as an advocate for

climate change adaptation generally and within the individual bodies represented

on the Committee

5) Ensure the bodies represented on the

Committee are adequately informed of adaptation activity in Te Taitokerau and

the rationale for these activities

6) Ensure the importance of and the

rationale for climate change adaptation is communicated consistently within Te

Taitokerau

7) Receive progress reports from the Te

Taitokerau Councils Climate Change Adaption Group

Membership

The Joint Climate Change Adaptation Committee (the committee)

is a standing committee made up of elected members from the Far North, Kaipara

and Whangarei district councils, the Northland Regional Council and

representatives from Northland hapū and iwi.

The committee shall have eight members as follows:

One elected member from: Kaipara

District Council

Far

North District Council

Whangarei

District Council

Northland Regional Council

Iwi / hapū members: One

representative from iwi / hapū nominated by each council from within their

jurisdiction. Where possible, this nomination should follow recommendations

from council Māori advisory groups or committees.

Each council shall also nominate one alternative elected

member and one alternative iwi / hapū member who will have full speaking

and voting rights when formally acting as the alternate.

Status

The Committee is a joint standing committee of council as

provided for under Clause 30(1)(b) of Schedule 7 of the Local Government Act

2002 and shall operate in accordance with the provisions of Clause 30A of that

Act. The committee is an advisory body only and has no powers under the Local

Government Act 2002 (or any other Act) other than those delegated by decision

of all member councils. The joint standing committee shall operate under

Northland Regional Council Standing Orders.

Committee Chair and deputy Chair:

The Chair and Deputy Chair is to be elected from members at

the first meeting of the committee.

Quorum

At least 50% of members shall be present to form a quorum.

Meetings

The Committee shall meet a minimum of two times per annum.

Service of meetings:

The

Northland Regional Council will provide secretarial and administrative support

to the joint committee.

Draft

agendas are to be prepared by the Te Taitokerau Councils Climate Change

Adaption Group and approved by the Chair of the Committee prior to the

Committee meeting.

Remuneration

Remuneration and / or reimbursement for costs incurred by

council members is the responsibility of each council.

Respective iwi / hapū representatives will be remunerated

and reimbursed by the nominating council in accordance with the Northland

Regional Council Non-Elected Members Remuneration Policy.

Amendments

Any amendment to the Terms of Reference or other arrangements

of the Committee shall be subject to approval by all member councils.

4.2 Options

Report - Parks and Reserves General Policies Development

File

Number: A2885500

Author: Caitlin

Thomas, Strategic Planner

Authoriser: Darrell

Sargent, General Manager - Strategic Planning and Policy

Purpose of the Report

For the Strategy and

Policy Committee to consider an analysis of options for the appropriate

management of parks and reserves through policies, and to make a recommendation

to Council for adoption of the most appropriate option. A detailed discussion

of options is contained in the attached report.

Executive Summary

· Parks and Reserves are lands’ that form Council’s open

space suite. Reserves are lands that are classified under the Reserves Act 1977

for a specific purpose, whereas parks are lands that are held for reserve

purposes but have not been classified under the Reserves Act.

· The current Reserves Policy was adopted by Council in 2017 as an

amalgamation of nine former reserves-related policies. The problem definition

and issues and options study, which led to Council’s May 2020 resolution

to develop a new reserve bylaw, identified several concerns and problems

arising from the 2017 policy amalgamation, including the omission to seek

public input, distinction between reserves and park lands, lack of clarity and

incorporation of regulatory provisions and standard operating procedures, while

other critical content was removed. The review of the current Reserve Policy

further identified inconsistencies with legislation, delegations and as a

result has been deemed not fit for purpose.

· The attached report discusses identified shortfalls and provides two

options to proceed with the management of parks and reserves through the use of

policy. The options discuss:

1. Do nothing/status quo (retain the 2017 Reserves Policy Document);

2.

Develop new General Policies for Parks and Reserves.

· Administration recommends Option 2.

|

Recommendation

The Strategy and

Policy Committee agrees and recommends to Council that new general policies

for the management of parks and reserves be developed.

|

1) Background

The problem definition

and issues and options analysis for the management and regulation of parks and

reserves, which, on May 15 2020, led to Council’s resolution to develop a

new Parks and Reserve Bylaw, included the review of the current Reserve Policy.

The Reserve Policy was

adopted by Council in March 2017, based on the amalgamation of nine former

reserve-related policies. The review of the policy identified several

concerns and problems arising from the 2017 policy amalgamation, including the

omission to seek public input on matters of significance, distinction between

reserves and park lands and their management requirements, lack of clarity,

incorporation of regulatory provisions and standard operating procedures, while

other critical content was removed. The review of the current Reserve Policy

further identified omissions of former content, inconsistencies with

legislation and matters of delegations for decision-making.

The review found that the

Reserve Policy does not create well-developed statements of position on ongoing

or recurring matters or provide direction for responses or actions of staff, or

for decisions of Council or a Committee.

The current Reserve Policy is attached to this report.

2) Discussion and Options

Brief Summary of Issues/Context

Council’s options

for the management of reserves and Council-owned lands which fulfil a similar

function but are not classified under the Reserve Act include:

· retaining

the status quo, i.e. continue with the implementation of the current Reserve

Policy, and

· developing

new general parks and reserves policies, to better address the identified

problems and provide improved community outcomes.

The attached issues and

options report provides a detailed discussion of identified problems and their

impact on decision-making and operations. A summary is provided below:

· The

amalgamation resulted in changes in content, including omission or removal of

policies which are deemed to be significant. At the time, no public

consultation was undertaken. As a result, the Reserve Policy is not

reflective of community needs and aspirations for parks and reserve lands.

· The

Reserve Policy refers to reserves only in its title, omitting non-classified

parks. It is important to distinguish between classified and non-classified

reserves, given their dedicated purpose and different management regimes

subject to applicable legislation. This impacts and confuses dialogue

with the public with respect to opportunities and constraints of these lands.

· Conversely,

other lands that do not form part of the open space suite ( for example the

road corridor) are address in the Reserve Policy, but should be removed.

· Some

content is inconsistent with if not contrary to applicable legislation

including the Reserves Act 1977, the Local Government Act 2002 or the Resource

Management Act 1991, or not give effect to National or Regional Policy

Statements.

· Whilst

discussed, supporting documents to standardize processes and operating

procedures were not created and remain unavailable. This results in

inconsistent responses and administration of parks and reserve management.

· Some

content of Reserve Policy is regulatory in nature and should be contained in a

bylaw rather than a policy.

· Terminology

is used interchangeably throughout causing a lack of clear direction if not

confusion.

· Some

content restricts elected members in the exercise of their delegations.

Reason

for the recommendation

Developing new parks and

reserves general policies is recommended in accordance with applicable

legislation including the Reserves Act 1977, the Local Government Act 2002, the

Resource Management Act 1991 and Heritage New Zealand/Pouhere Taonga Act 2014.

Reasons for this

recommendation include the development of a fit for purpose policy, which:

· Is

compliant with legislation,

· Considers

both classified reserves and parks,

· Is

consistent with the District Plan and enables the development of future

Engineering Standards, future Parks and Reserves Bylaw, and standard operating

procedures and processes etc,

· Follows

best-practice while being locally relevant,

· Provides

policy statements for all identified matters and problems requiring guidance

and direction.

3) Financial Implications and Budgetary

Provision

The development of new

parks and reserves general policies will not immediately indicate any financial

implications and can be completed within current budgets.

Attachments

1. Options Report

Parks and Reserves General Policies Review and Development - A2910437 ⇩

2. Far North

District Council Reserves Policy 2017 - A2905609 ⇩

Compliance schedule:

Full consideration has

been given to the provisions of the Local Government Act 2002 S77 in relation

to decision making, in particular:

1. A Local authority

must, in the course of the decision-making process,

a) Seek to identify all

reasonably practicable options for the achievement of the objective of a

decision; and

b) Assess the options in

terms of their advantages and disadvantages; and

c) If any of the options

identified under paragraph (a) involves a significant decision in relation to

land or a body of water, take into account the relationship of Māori and

their culture and traditions with their ancestral land, water sites, waahi

tapu, valued flora and fauna and other taonga.

2. This section is

subject to Section 79 - Compliance with procedures in relation to decisions.

|

Compliance

requirement

|

Staff

assessment

|

|

State

the level of significance (high or low) of the issue or proposal as

determined by the Council’s

Significance and Engagement Policy

|

This

meets a High Significance threshold as the proposal will likely generate

considerable community interest.

|

|

State

the relevant Council policies (external or internal), legislation, and/or

community outcomes (as stated in the LTP) that relate to this decision.

|

Reserves

Act 1977 – section 3, and 41 which relate to creation of policy in the

process of developing Reserve Management Plans.

Local

Government Act 2002 – sections 3, 4, 11A, 77, 145, 146 and 149.

Te

Tiriti o Waitangi – section 4.

Heritage

NZ/Pouhere Taonga Act 2014 – section 3.

Resource

Management Act 1991 and NZCPS.

NPS

– Urban Development, Indigenous Biodiversity.

District

Plans – Open Space/Zones

Northland

Regional Policy Statements - various.

Contribution

towards meeting community outcomes (as stated in the LTP) by way of a safe

and healthy district, a sustainable and liveable environment, and a vibrant

and thriving economy through thorough decision making as it relates to the

management and operations of Councils parks and reserves.

|

|

State

whether this issue or proposal has a District wide relevance and, if not, the

ways in which the appropriate Community Board’s views have been sought.

|

This

proposal has District wide relevance.

|

|

State the possible implications for

Māori and how Māori have been provided with an opportunity to

contribute to decision making if this decision is significant and relates to

land and/or any body of water.

|

There

are implications for Māori as this relates to the activities on public

land and in some instances, adjacent bodies of water. It is recommended that

key stakeholder engagement with Māori is conducted in the drafting of

policies.

|

|

Identify

persons likely to be affected by or have an interest in the matter, and how

you have given consideration to their views or preferences (for example

– youth, the aged and those with disabilities.

|

Many

parties in the community will be interested or consider themselves affected

including individuals as well as special interests groups and organisations

such as: mana whenua and tangata whenua iwi (see Iwi/Hapu Management Plans),

Heritage NZ/Pouhere Taonga, User groups; lessees and licensees, sports

and recreation clubs and general users of facilities – including

children, the elderly and those with disabilities), event managers.

Management groups – Hall Management committees etc, Health Department,

Northland Regional Council, Department of Conservation, Advocacy Groups

– e.g. Vision Kerikeri, Friends of Kerikeri Domain, Rotary Groups etc.

Special interest groups – Forest and Bird, Bay of Island Watchdogs,

Walking Access. Tourism Association. It is recommended that other key

stakeholder engagement is conducted in the drafting of the bylaw.

|

|

State

the financial implications and where budgetary provisions have been made to

support this decision.

|

Currently

there are no financial implications.

|

|

Chief

Financial Officer review.

|

The

Chief Financial Officer has reviewed this report.

|

|

Strategy and Policy Committee Meeting Agenda

|

30 July 2020

|

|

Strategy and Policy

Committee Meeting Agenda

|

30 July 2020

|

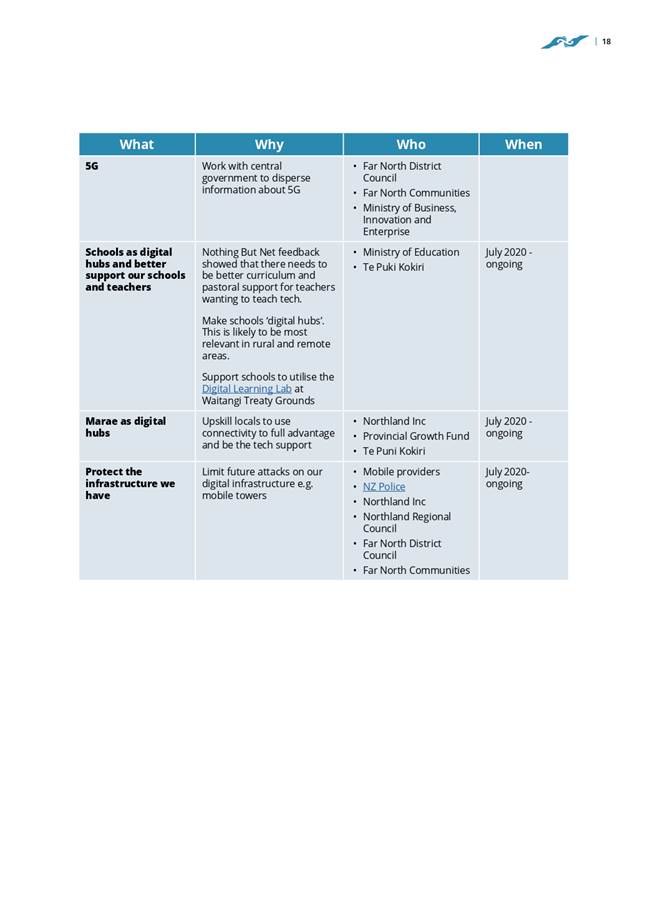

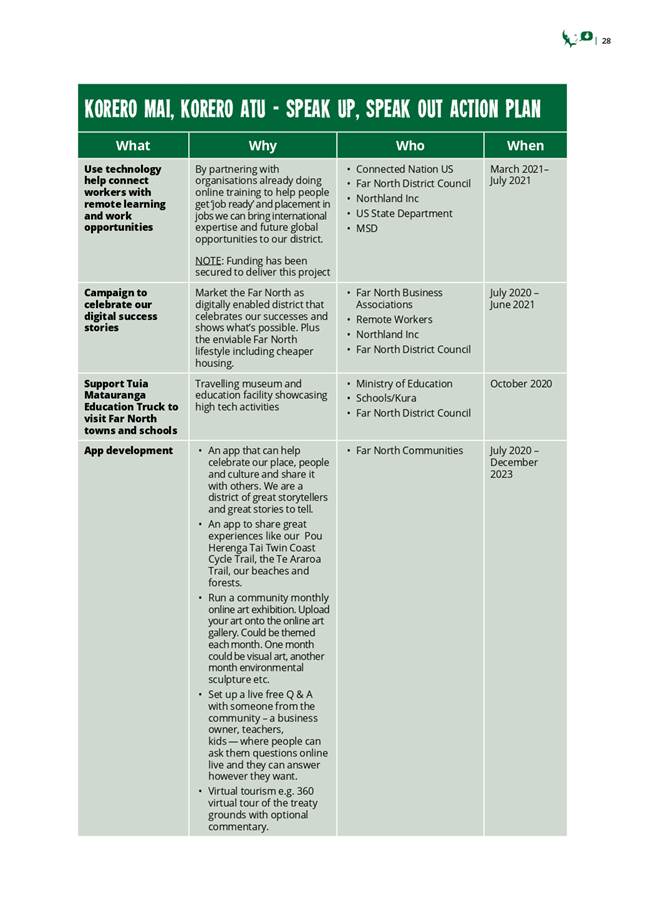

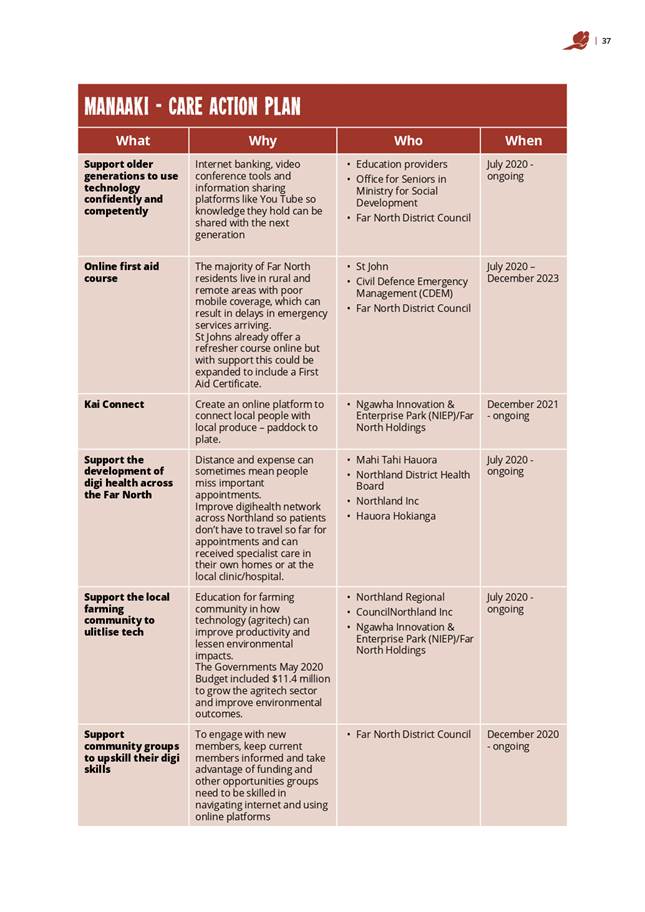

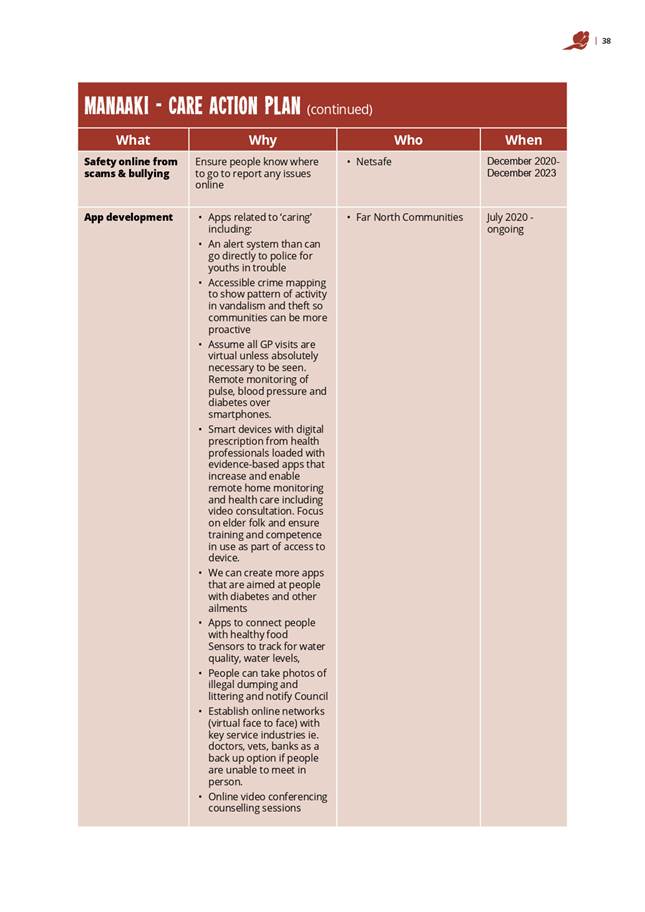

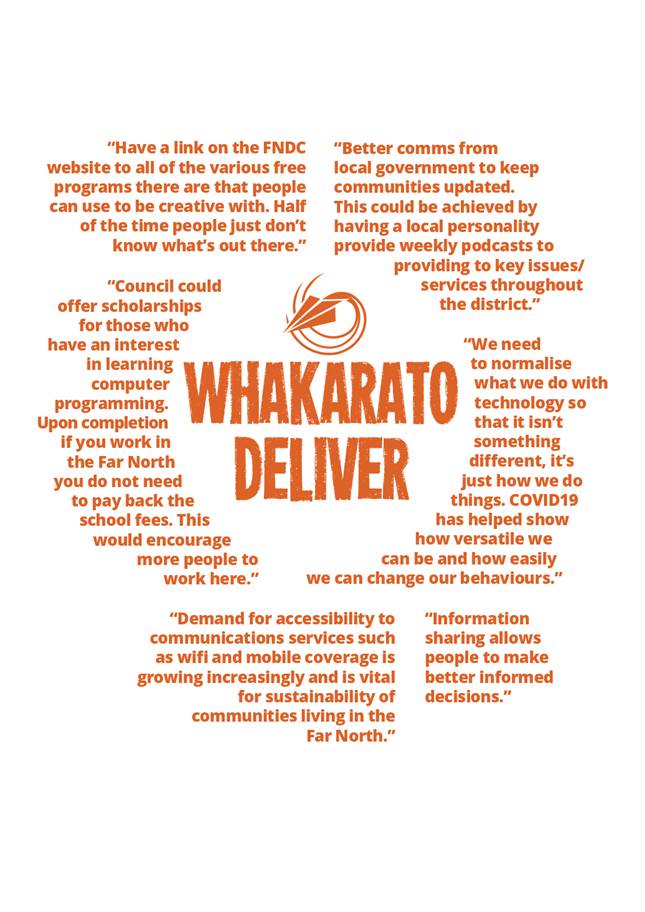

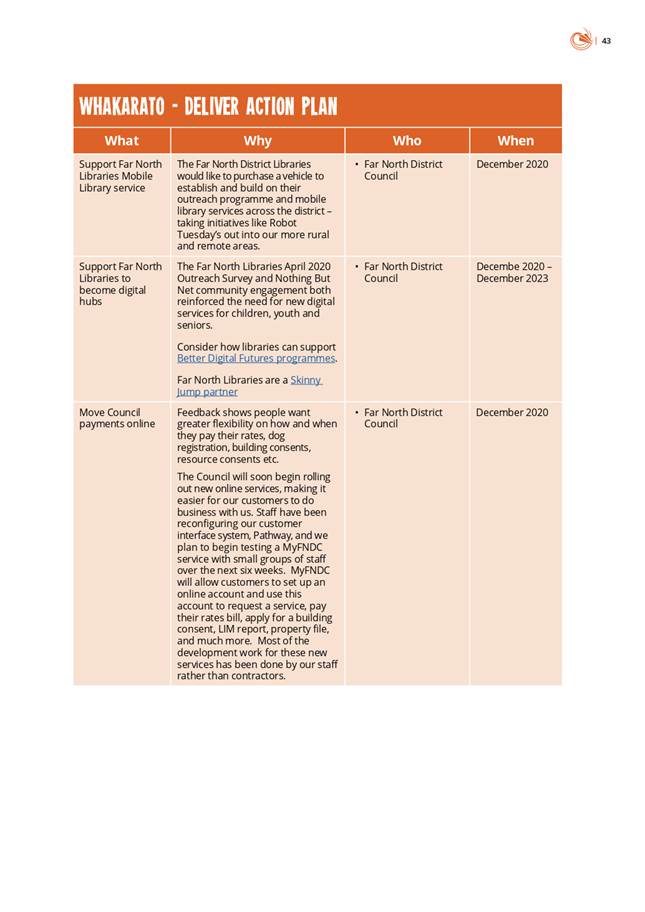

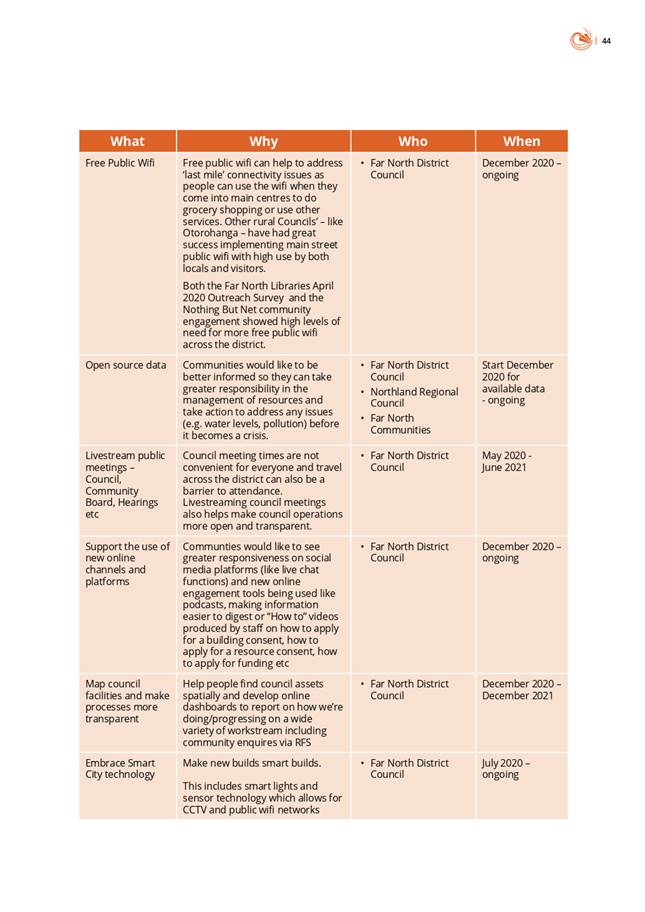

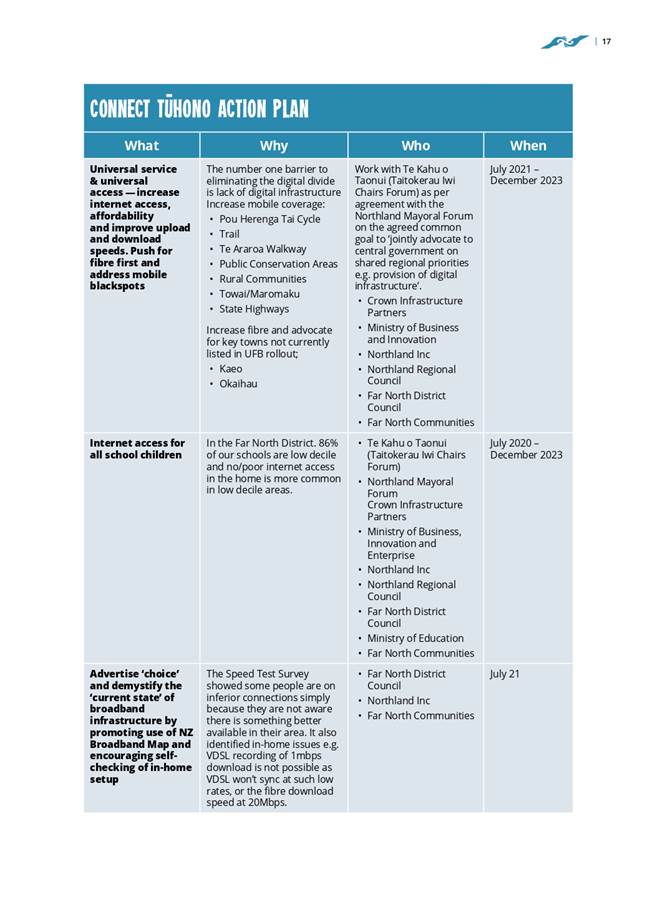

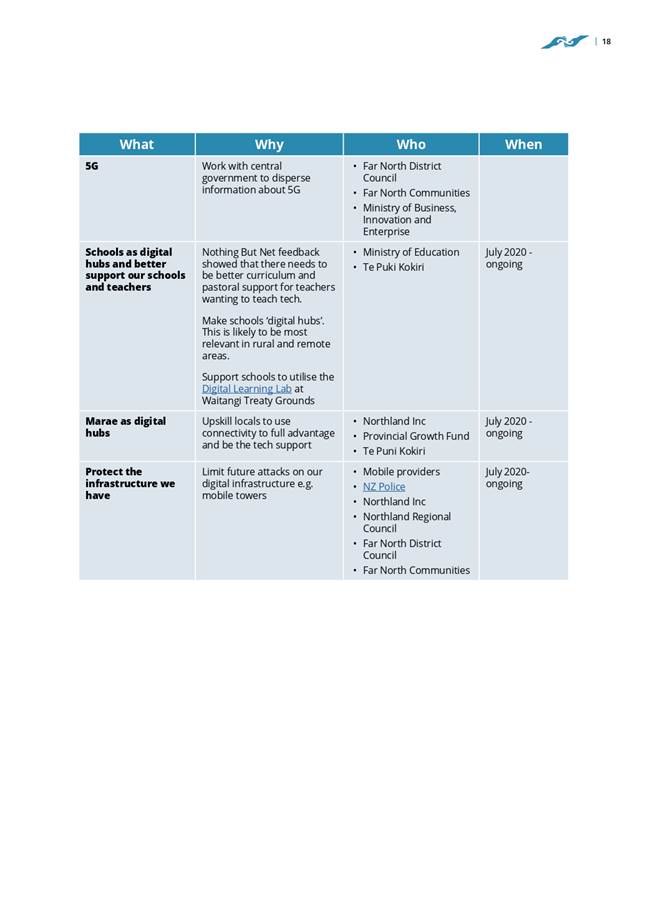

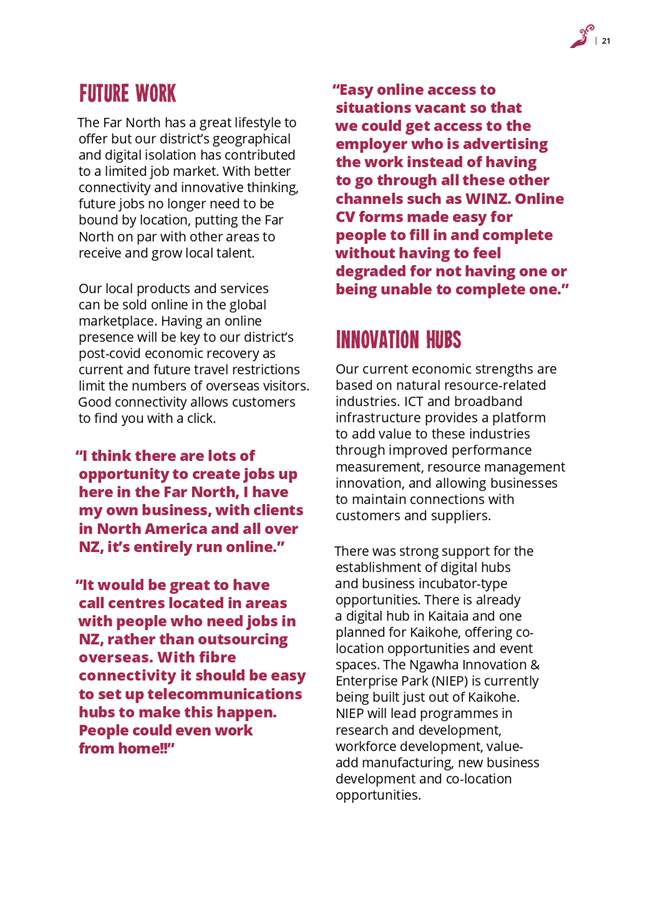

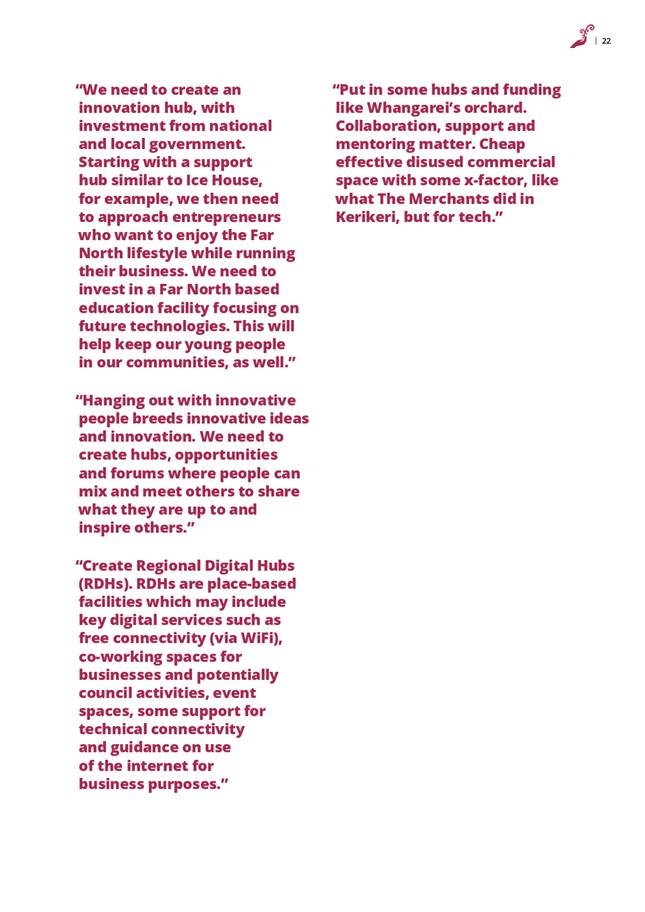

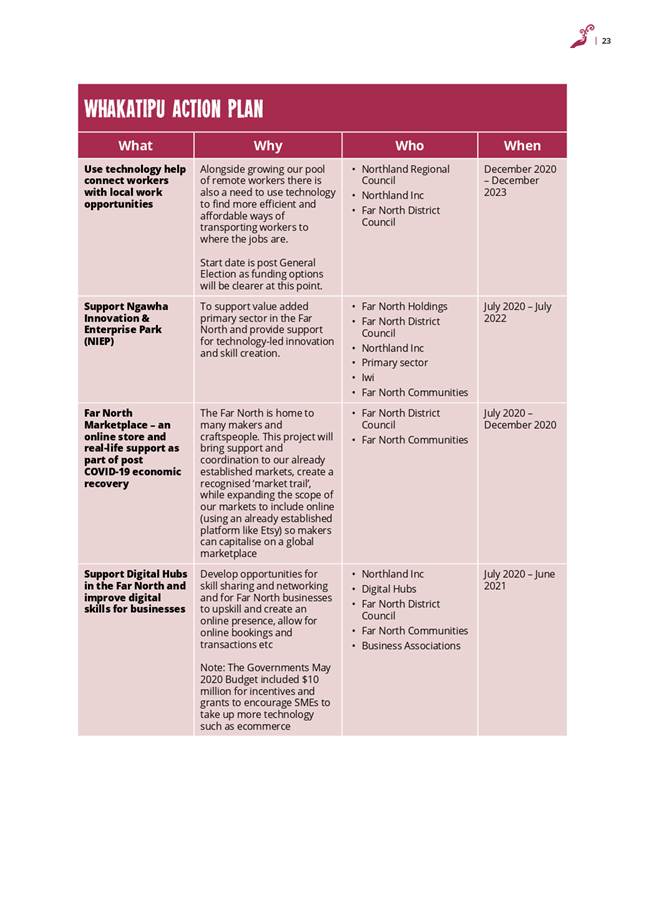

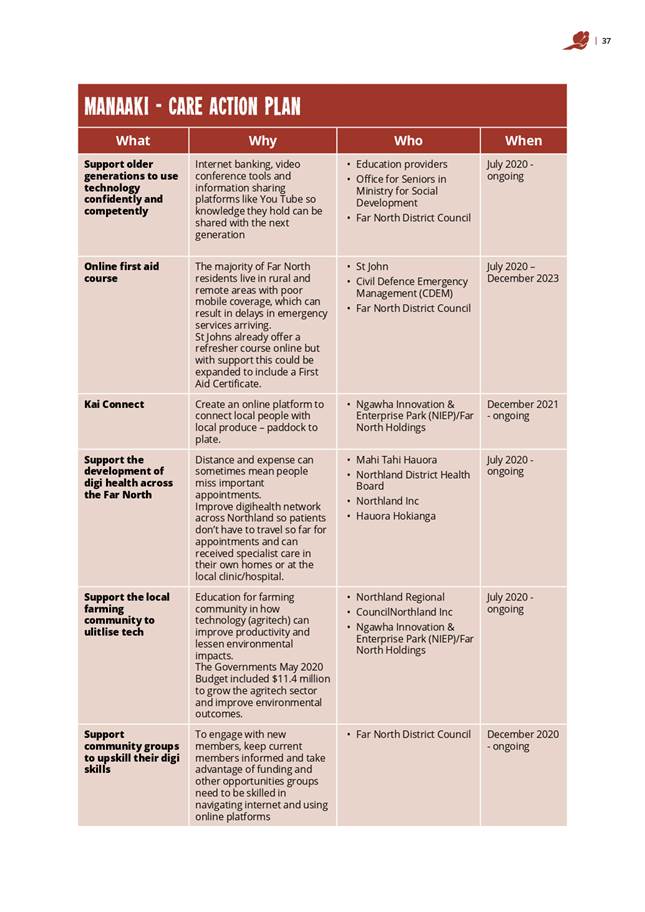

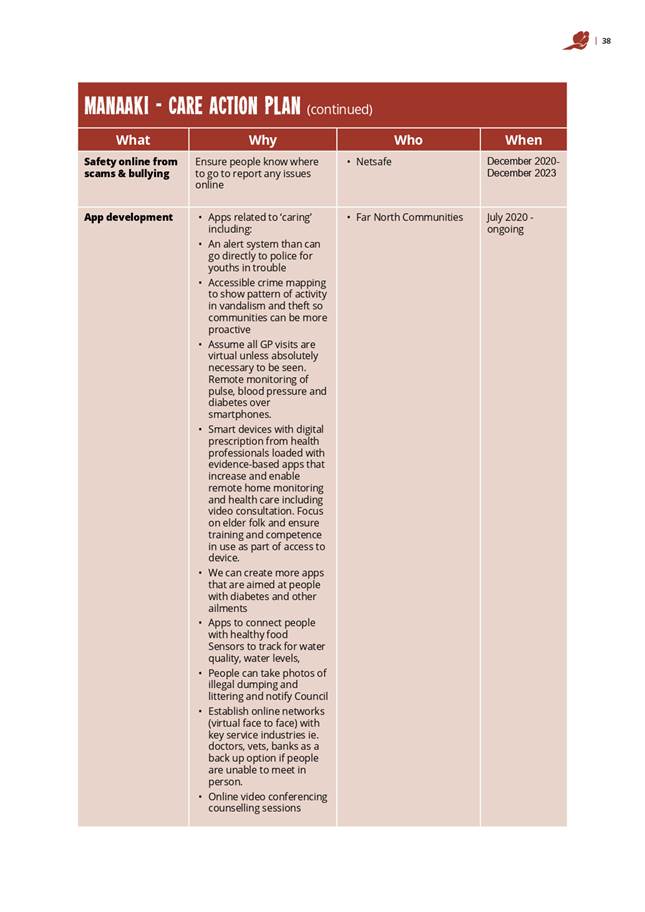

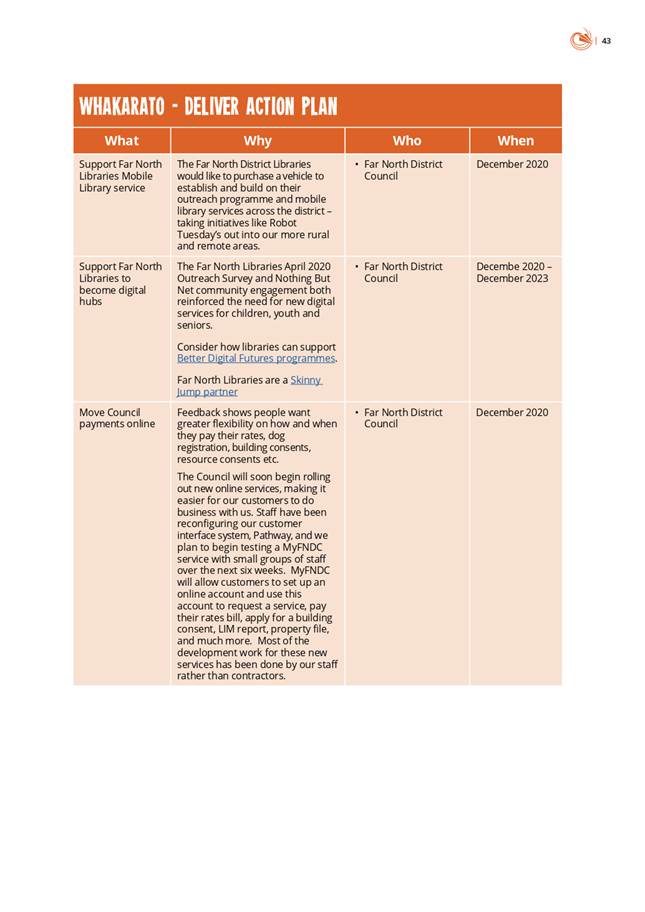

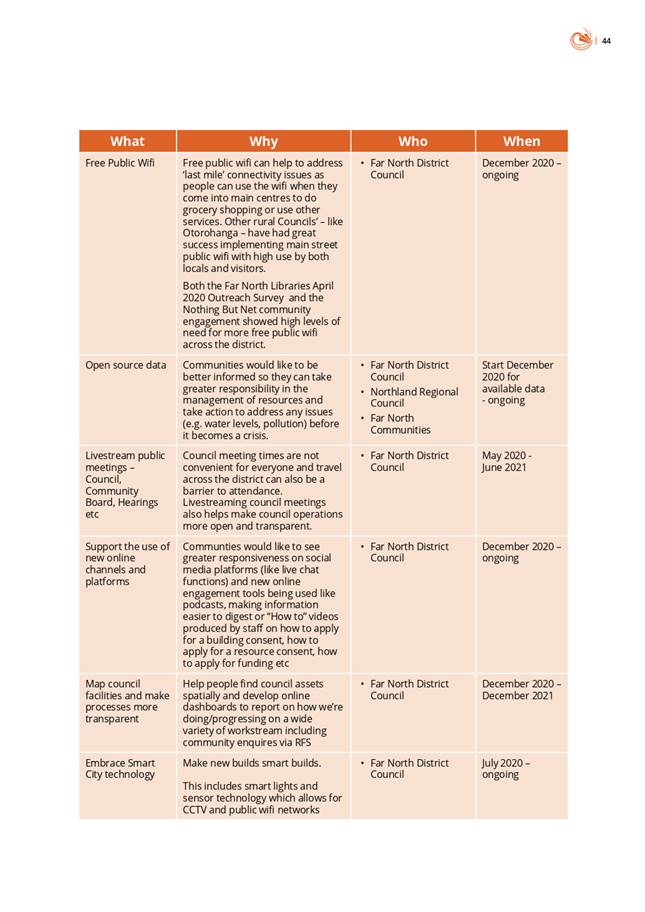

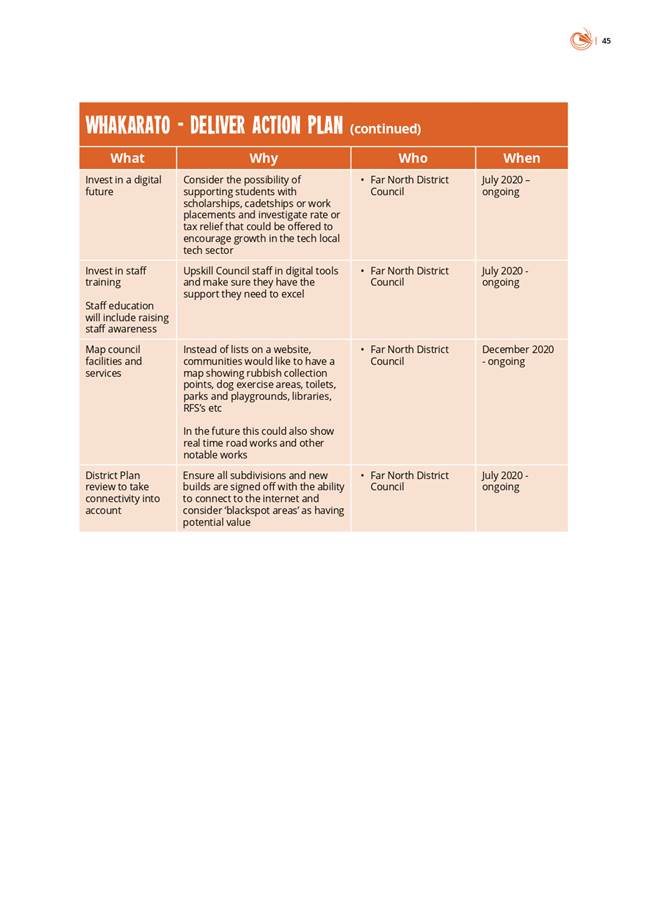

4.3 Nothing

But Net Far North Digital Strategy

File

Number: A2905122

Author: Ana

Mules, Team Leader - Community Development and Investment

Authoriser: Darrell

Sargent, General Manager - Strategic Planning and Policy

Purpose of the Report

To present the Nothing

But Net Far North Digital Strategy to the Strategy and Policy Committee.

Executive Summary

· There

is an increasing reliance on digital and those without connectivity or the

skills to use it risk getting further left behind.

· The

COVID-19 pandemic and resulting nationwide lockdown further exposed the digital

divide across Northland.

· This

digital strategy & action plan was developed with input from internal and

external reference groups and the public via a digital campaign called Nothing

But Net.

· The

strategy recommends immediate actions to address the digital divide in the Far

North.

|

Recommendation

That the Strategy

and Policy Committee recommend that Council adopt the Nothing But Net Far

North Digital Strategy and commits to delivering on the actions in the plan

as part of the 2021-2031 Long Term Plan.

|

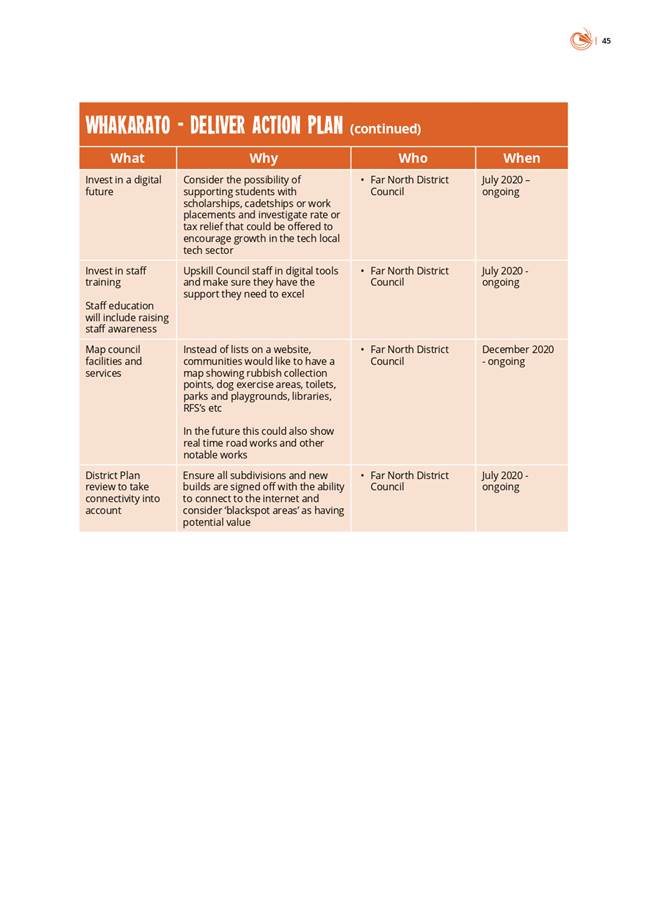

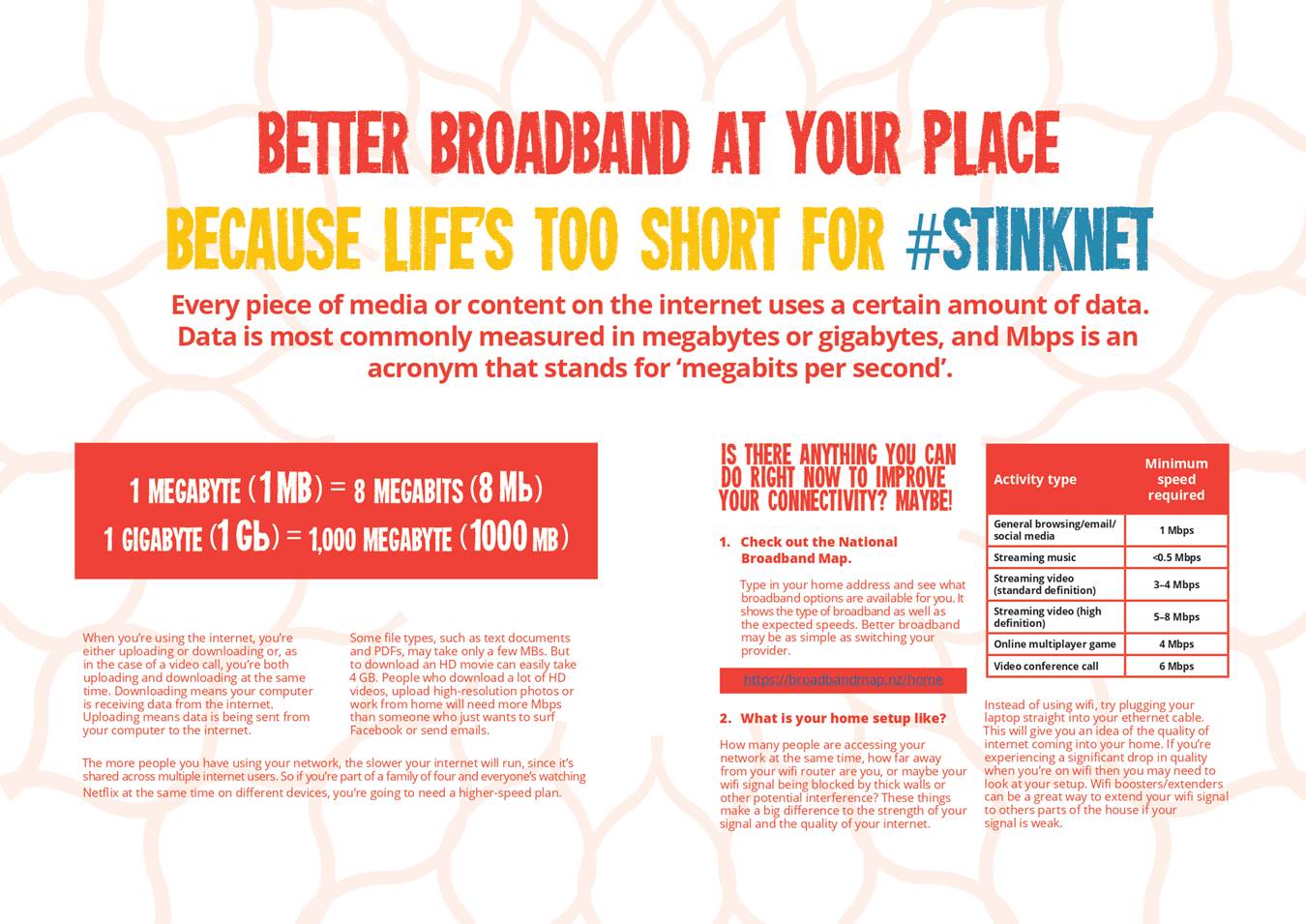

Background

The digital divide is the

gap between those who have connectivity and the skills to use it and those who

do not. It is the result of inadequate or lacking digital infrastructure,

difficulties in access and affordability, poor digital literacy and capability

and relevance. The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting nationwide lockdown has

further exposed the digital divide across Northland.

In response to the

digital challenges faced by our communities in lockdown, and while connectivity

and digital skills were top of mind, staff considered it an opportune time to

start a conversation about how we could become a more digitally enabled

district. Using co-design methodologies and a new and innovative online

engagement tool (Video Ask), people were asked a series of

questions that linked the 4 wellbeing’s and digital connectivity.

Called ‘Nothing But

Net’, engagement ran for a 2-week period (1 May - 15 May) and 118 full

and complete responses (i.e. all 9 questions answered) were submitted over this

time. Hundreds more submitted answers to a few questions only or simply

‘clicked through’ to find out more. There were well over 1000

individual responses in total.

In addition to the

qualitative data collected through Nothing But Net, the Northland Digital

Enablement Group’s annual Broadband Speed Test Surveys (2016-2020)

provide quantitative data on broadband speeds and insight into ongoing

infrastructure challenges. Both these pieces of work actively involved key stakeholders, enabling and empowering

the people affected by the issues to contribute to developing the solutions, and they have helped inform this

piece of work, the Nothing But Net Far North Digital Strategy.

The ‘Nothing But

Net’ strategy and action plan is a 3.5 year plan that that will be used

to support our district’s digital future by directly addressing the

digital divide. Internal and

external reference groups have been established to provide feedback

and guidance and care has been taken to ensure Nothing But Net meets the

immediate needs of our communities.

The strategy content and

structure is a direct result of community contributions and an external

reference group of industry professionals. The final draft was presented back

to all contributors for refinement. This iterative, co-design process has

ensured the resulting document is fit for purpose and reflects the ideas and

aspirations of our communities.

Discussion and Next Steps

Eliminating the digital divide in the Far North will take

many hands but with a strategy, organisations and

individuals can work together towards the shared goals of ensuring that

everyone is empowered by digital technology, our economy is supported, and no

one is left behind.

Staff ask that the

Strategy and Policy Committee receives the Nothing But Net Far North Digital

Strategy and recommend that Council adopts the Strategy and commits to

delivering on the actions in the plan as part of the 2021-2031 Long Term Plan.

Financial Implications and Budgetary Provision

There are no financial implications.

Attachments

1. NBN Final Version

Strat and Policy Committee 3 July 2020 - A2912339 ⇩

Compliance schedule:

Full consideration has been given to the provisions of the

Local Government Act 2002 S77 in relation to decision making, in particular:

1. A

Local authority must, in the course of the decision-making process,

a) Seek

to identify all reasonably practicable options for the achievement of the

objective of a decision; and

b) Assess

the options in terms of their advantages and disadvantages; and

c) If

any of the options identified under paragraph (a) involves a significant

decision in relation to land or a body of water, take into account the

relationship of Māori and their culture and traditions with their

ancestral land, water sites, waahi tapu, valued flora and fauna and other

taonga.

2. This

section is subject to Section 79 - Compliance with procedures in relation to

decisions.

|

Compliance

requirement

|

Staff

assessment

|

|

State the level of significance

(high or low) of the issue or proposal as determined by the Council’s Significance and Engagement Policy

|

Low degree of significance.

Initiatives/budget items allocated as a result of the strategy may be

considered significant but this will happen as part of Long Term or Annual

Planning.

|

|

State the relevant Council

policies (external or internal), legislation, and/or community outcomes (as

stated in the LTP) that relate to this decision.

|

Legislatively, this strategy

speaks to community wellbeing and the purpose of local government.

|

|

State whether this issue or

proposal has a District wide relevance and, if not, the ways in which the

appropriate Community Board’s views have been sought.

|

District-wide relevance.

Community Board views have not been sought. An external reference group of

industry professionals contributed significantly.

|

|

State the possible implications for Māori

and how Māori have been provided with an opportunity to contribute to

decision making if this decision is significant and relates to land and/or

any body of water.

|

Targeted engagement with iwi/hapu

was not carried out in the development of the strategy but iwi leaders were

provided with a copy of the draft and their feedback invited.

|

|

Identify persons likely to be

affected by or have an interest in the matter, and how you have given

consideration to their views or preferences (for example – youth, the

aged and those with disabilities.

|

Digital connectivity is an issue

that attracts a lot of attention in the Far North. Almost every household

will be affected by the outcomes of this strategy once it has been

implemented.

|

|

State the financial implications

and where budgetary provisions have been made to support this decision.

|

None. Future costs for the

implementation of the strategy will be taken through long term and/or annual

planning processes.

|

|

Chief Financial Officer review.

|

The Chief Financial Officer has

reviewed this report.

|

|

Strategy and Policy Committee Meeting Agenda

|

30 July 2020

|

5 Information

Reports

5.1 Section

35 Report - Review of the Efficiency and Effectiveness of the Operative Far

North District Plan

File

Number: A2870725

Author: Emily

Robinson, Policy Planner

Authoriser: Darrell

Sargent, General Manager - Strategic Planning and Policy

Purpose of the Report

To inform the Committee

of Council’s monitoring and reporting responsibilities under Section 35

of the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA), and for the Committee to receive the

report, “Review of Efficiency and Effectiveness of the Far North District

Plan”.

Executive

SummarY

Councils are required to

gather information, undertake monitoring and keep records in order to

effectively carry out their functions under Section 35 of the Resource

Management Act (1991). At least every 5 years, Council must prepare a report on

the efficiency and effectiveness of the rules, policies and other methods in

its plan, and make this report publicly available. The District Plan team have

prepared the Section 35 report to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of

the Operative District Plan in fulfilling the sustainable management purpose of

the RMA.

|

Recommendation

That the Strategy

and Policy Committee receive the report, “Section 35 Report - Review of

the Efficiency and Effectiveness of the Operative Far North District Plan under

Section 35 of the Resource Management Act”.

|

BackgrounD

Section 5 of the RMA (the

Act) establishes the purpose of the Act as being the sustainable management of

natural and physical resources by managing the use, development and protection

of these resources. Council’s are required under Section 35 of the Act to

produce a report at least every 5 years which reports on the efficiency and

effectiveness of policies, provisions and other methods within their plan. The

Section 35 reports draw on data gathered and reports kept from resource consent

applications, as well as monitoring programs that are undertaken to fulfil the

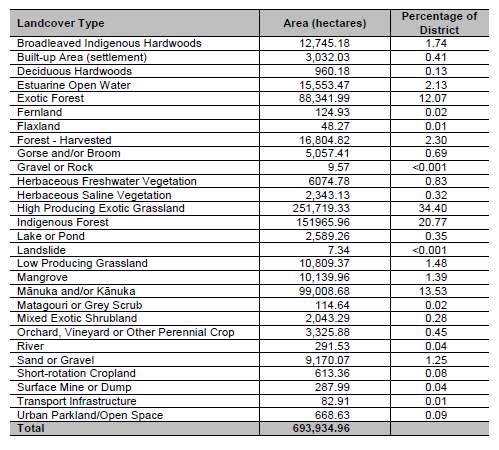

obligations of the RMA. The current report uses data from 2013 to 2018 in order

to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the District Plan.

Ø The

Operative Far North District Plan

The

Far North District Plan is the principal planning document to achieve the

sustainable management purpose of the Act. The Plan was mostly operative in

2007 and became fully operative in September 2009. As a previous Section 35

report focussed on the years preceding 2015, the current report will focus on

the 2013-2018 period. The report uses resource consent data from this period

gathered from internal and external sources and draws conclusions about the

efficiency and effectiveness of the Far North District Plan from this data.

Ø Purpose of the Section 35

Report

While

the principal purpose of the Section 35 report is to gauge the efficiency and

effectiveness of the District Plan, the report also enables Council the

opportunity to reflect and improve on internal processes by understanding

emerging trends in resource consent applications and associated monitoring

programs within the District. This also assists the District Plan team in their

authoring of Section 32 reports for the Proposed District Plan, due for

notification at the end of 2020. While there are many new

responsibilities and structural changes to the way plans must now be prepared

under the National Planning Standards, the analysis of plan efficiency and

effectiveness will directly inform the need for provisions and the relevant

thresholds for setting rules and associated performance standards for different

activities in the new District Plan.

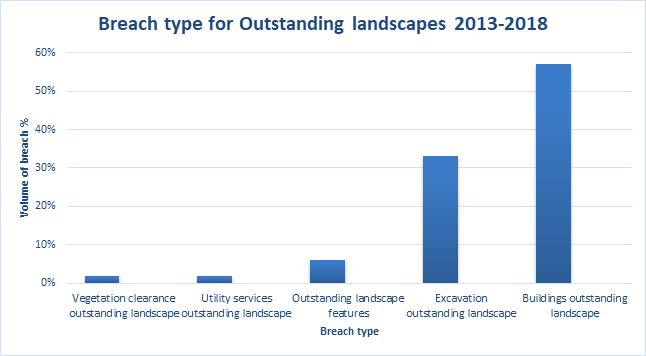

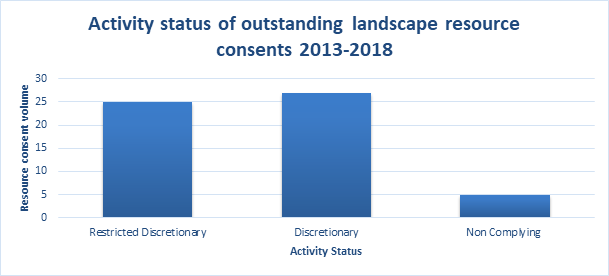

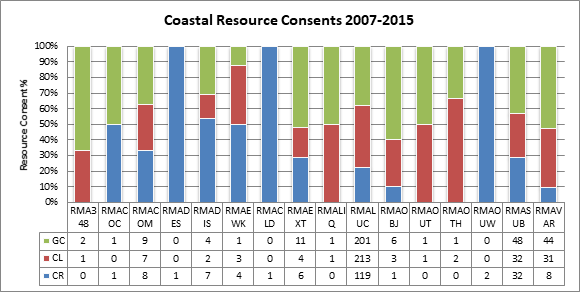

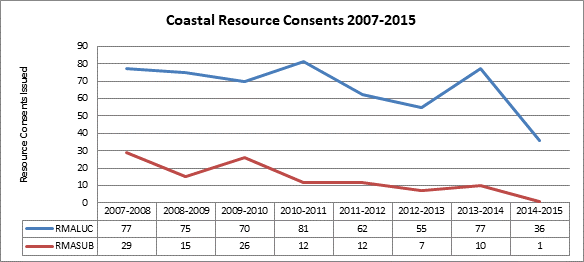

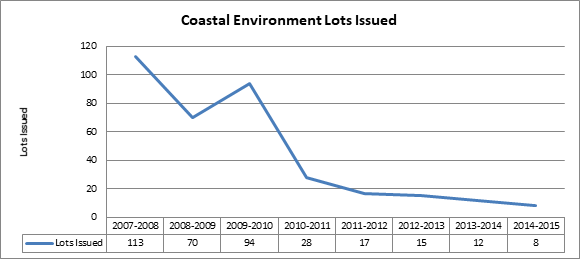

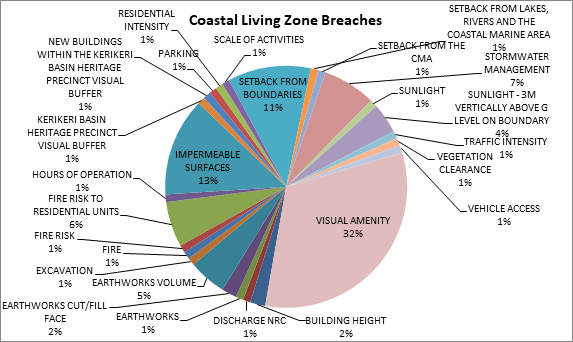

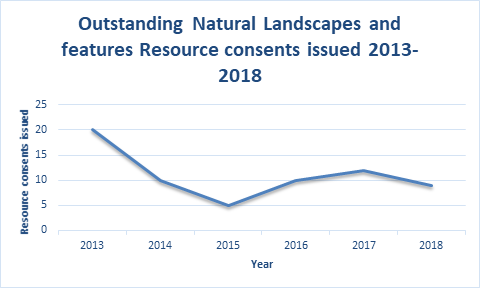

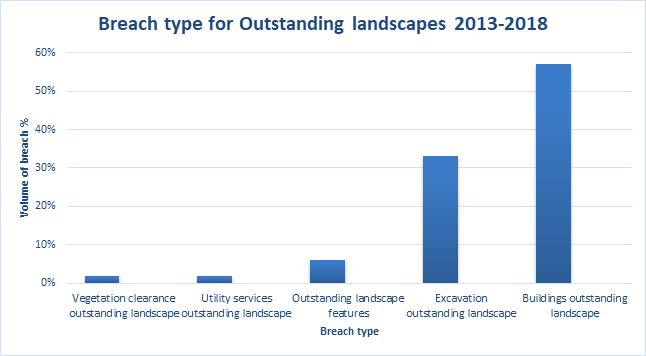

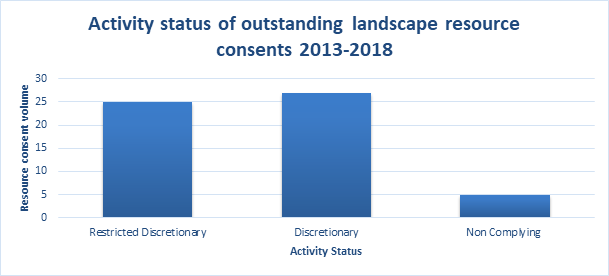

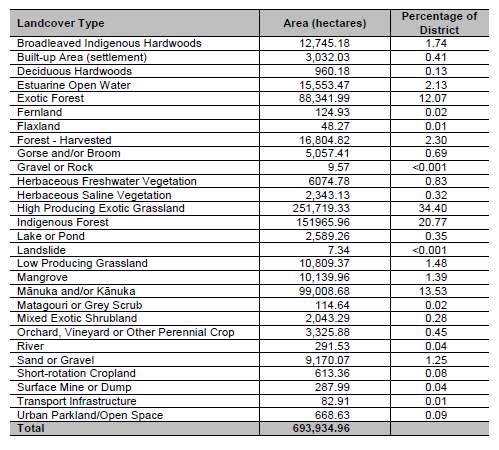

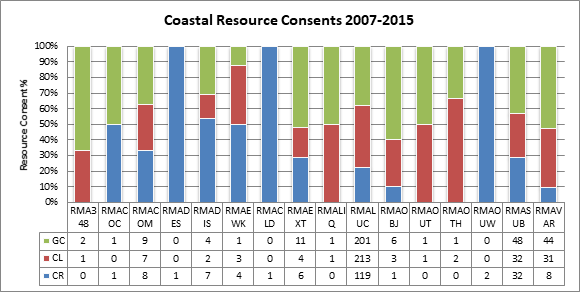

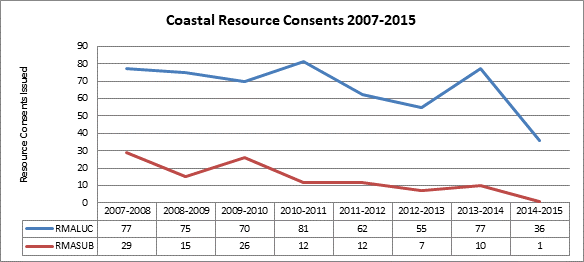

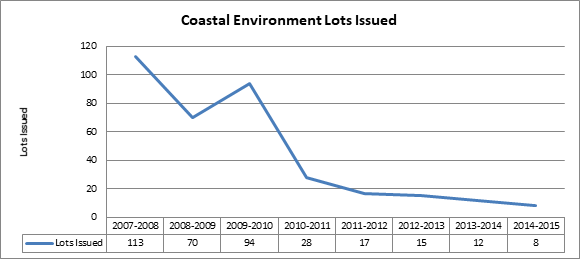

Ø Findings

and Conclusions of the Section 35 Report

The Section 35 report enables us to examine resource consent trends over

the period between 2013 and 2018. This analysis reports on both the efficiency

and effectiveness of the plan, while informing our plan making process. The

below trends emerged from the Section 35 analysis:

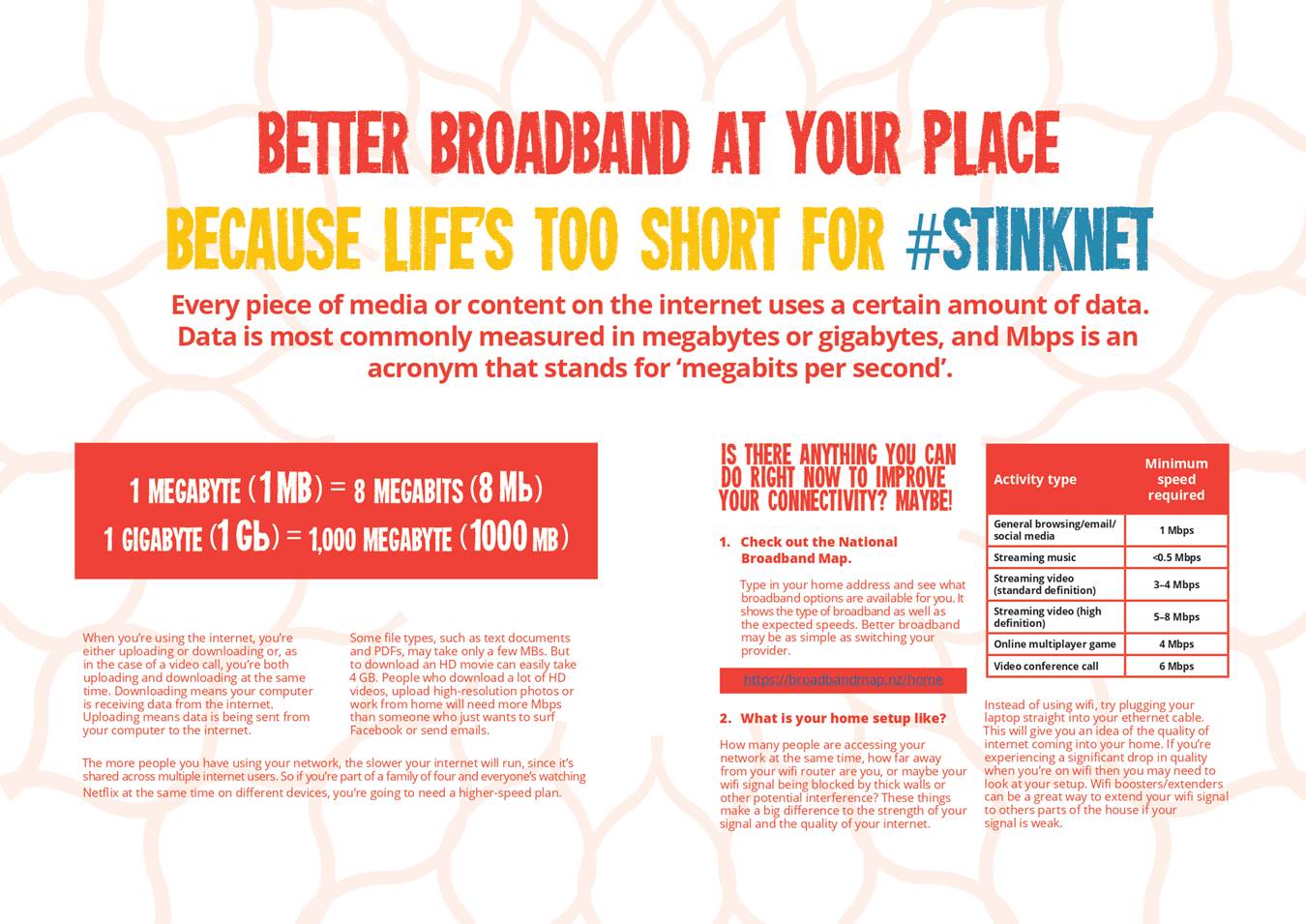

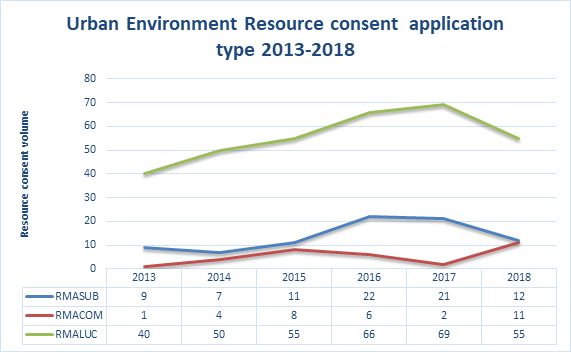

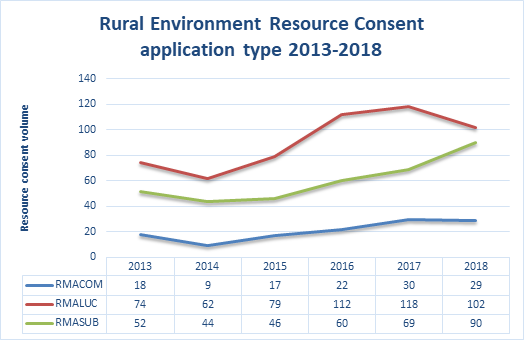

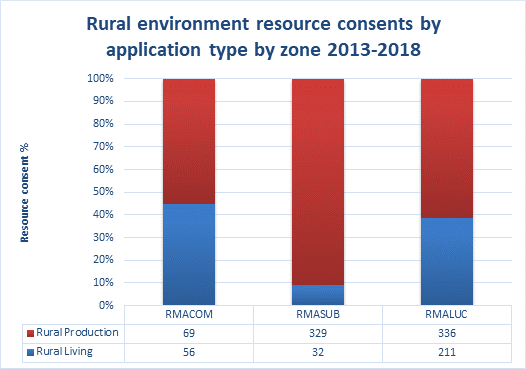

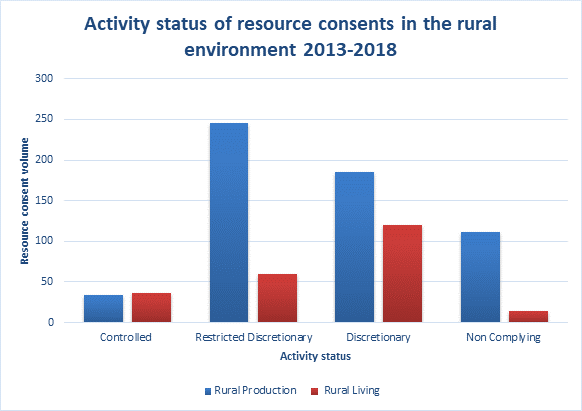

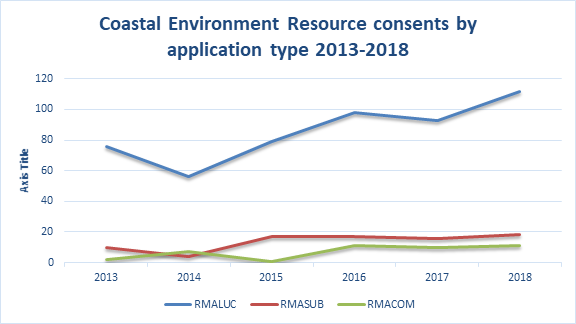

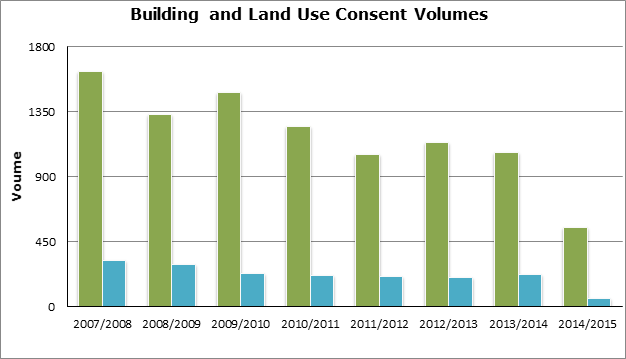

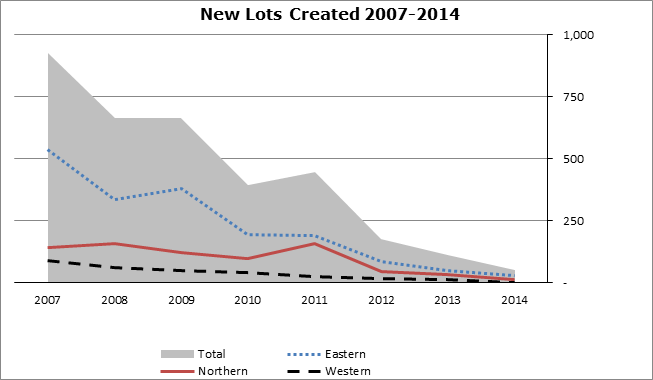

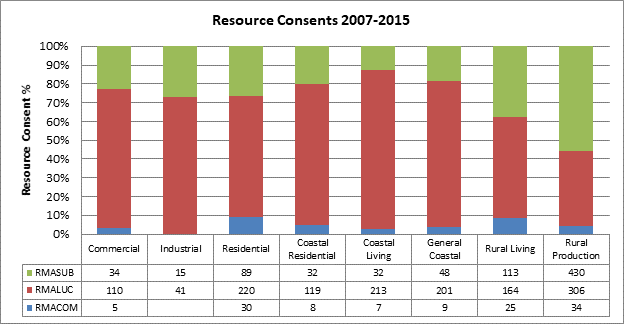

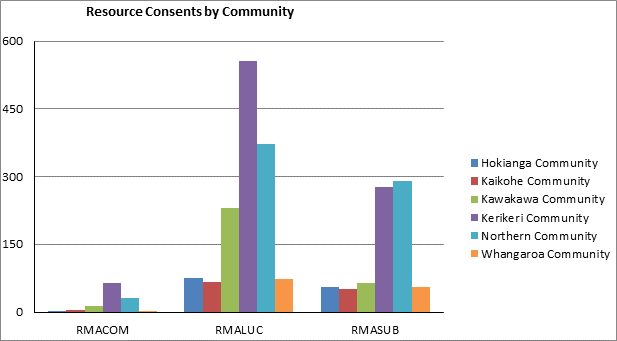

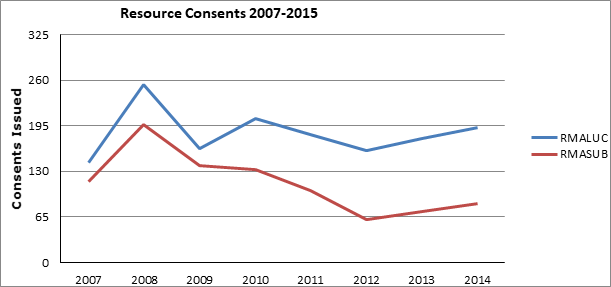

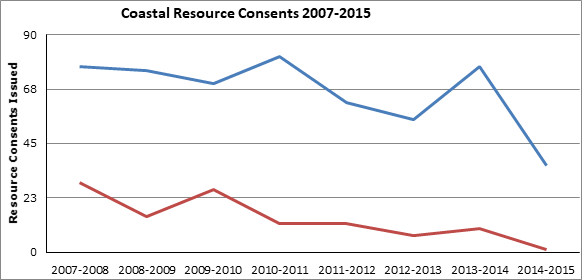

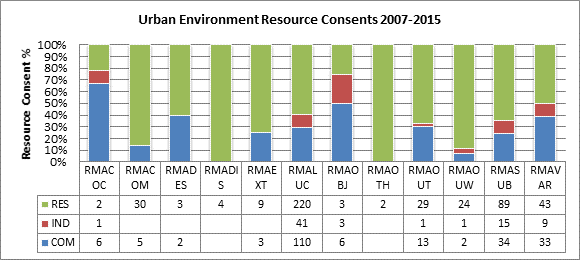

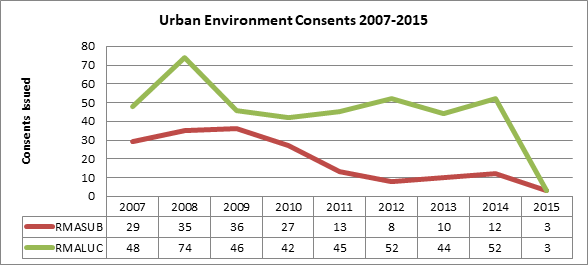

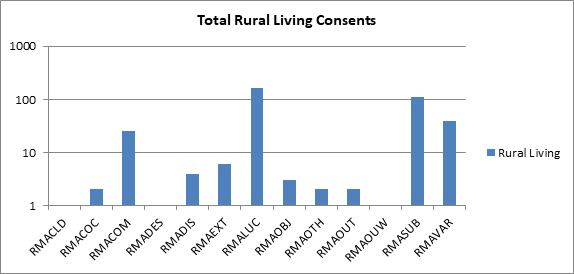

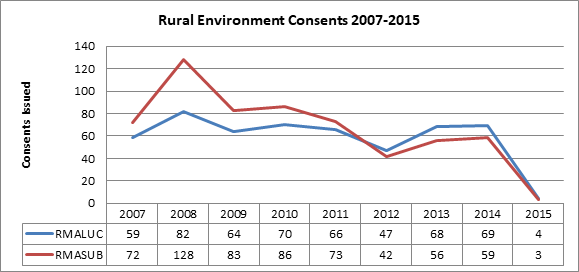

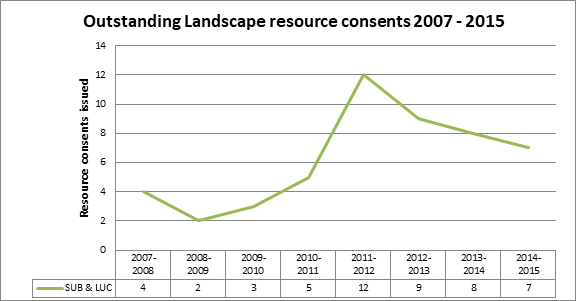

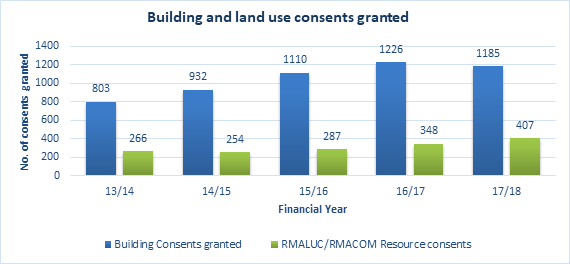

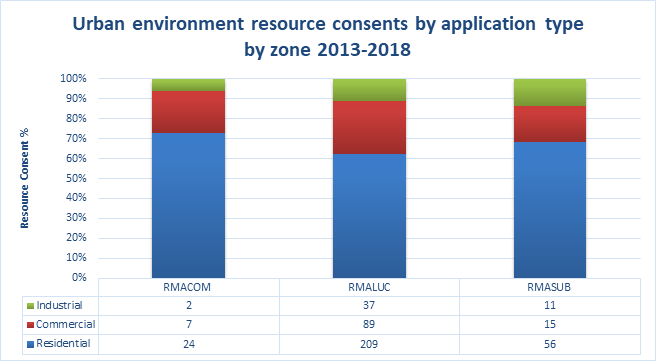

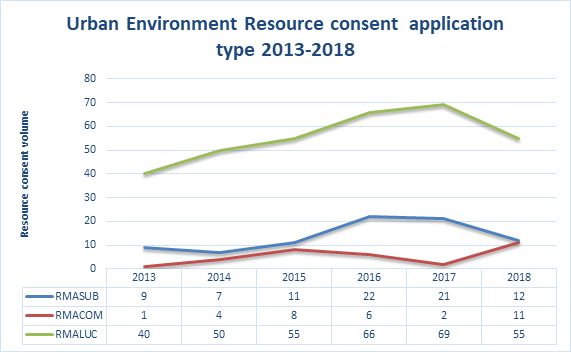

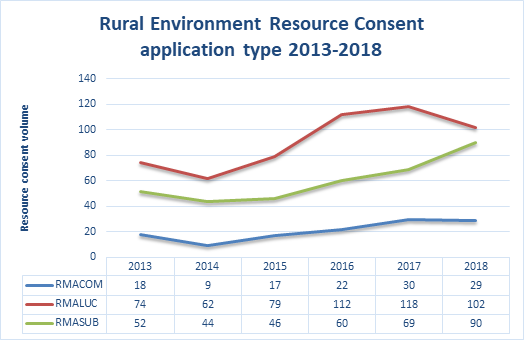

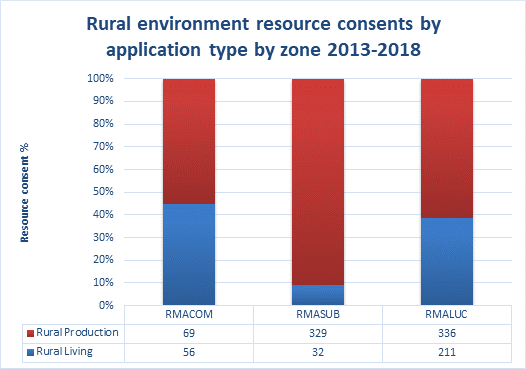

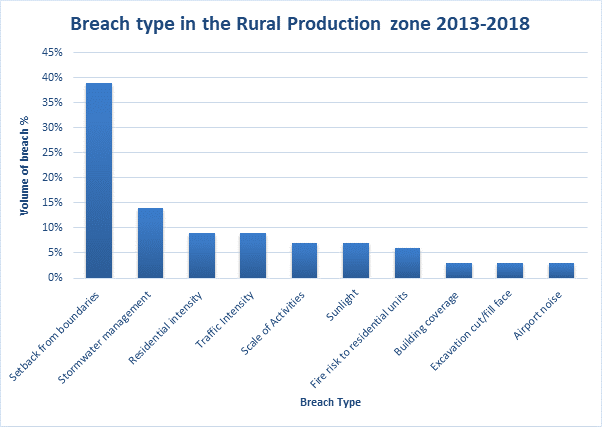

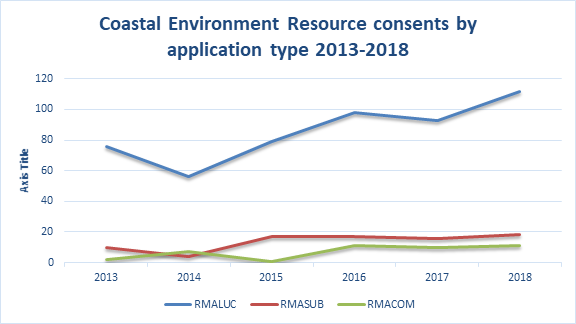

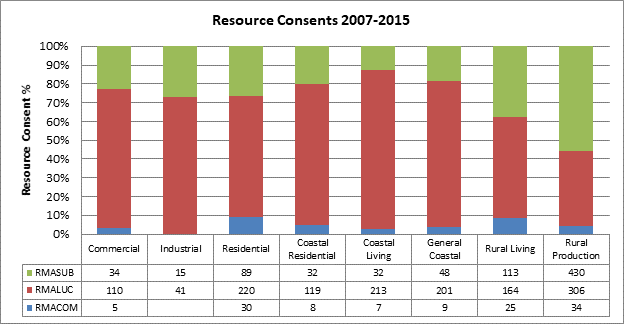

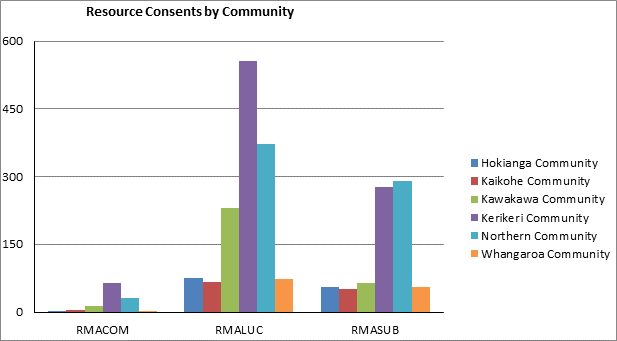

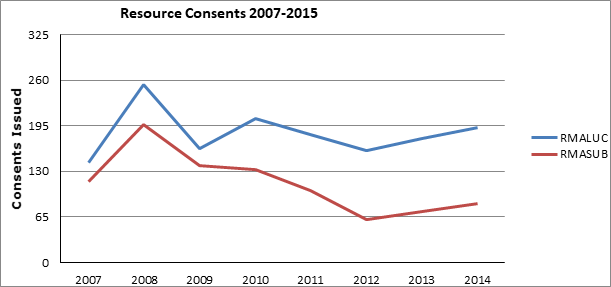

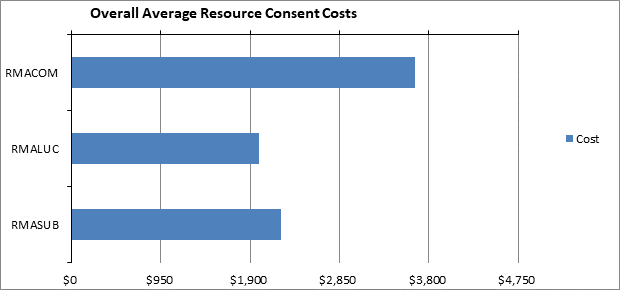

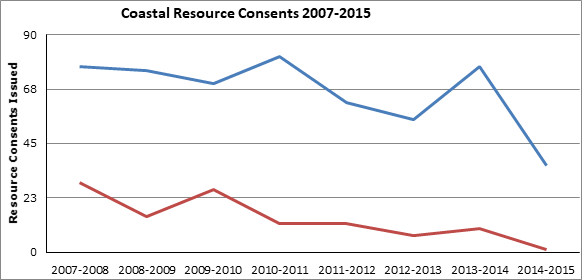

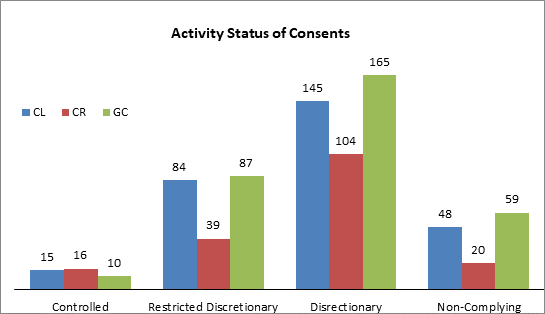

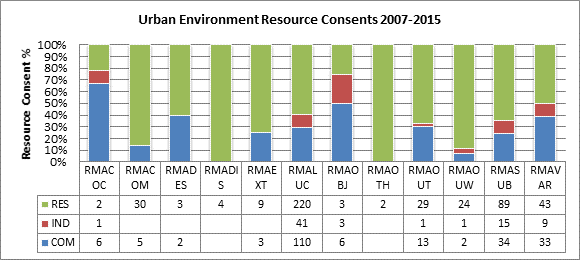

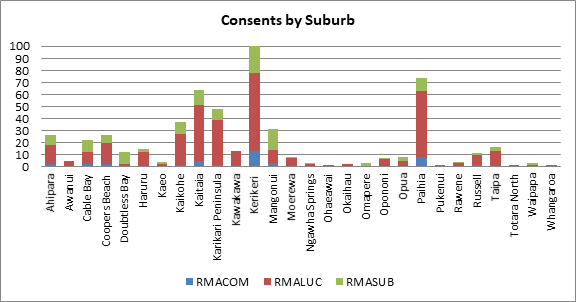

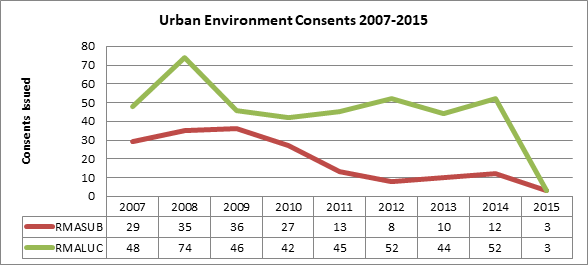

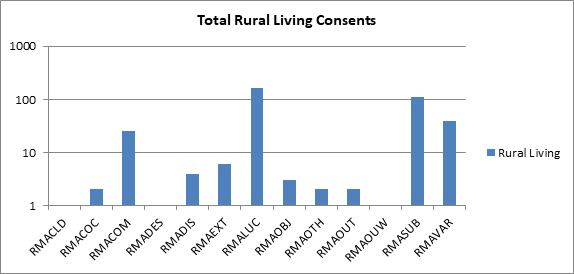

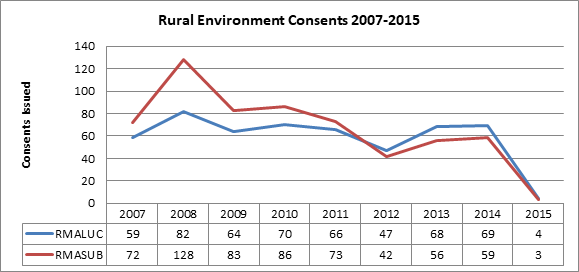

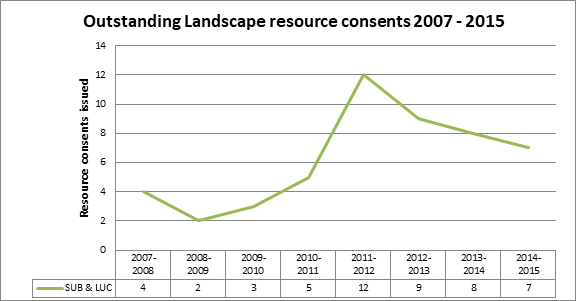

· The

number of resource consents granted per financial year has increased over the

past 5 years, with the largest proportion of resource consents occurring in the

rural environment. In particular, the Rural Production zone has seen the

largest number of resource consents for any one zone.

· The

large amount of consents in the rural environment enables us to gain an

understanding of the development pressures which exist in the Far North and can

be taken into account for the proposed District Plan. For example, an increase

in the amount of consents in the rural environment may indicate that development

is occurring where the plan does not anticipate it and this may be due to

factors including infrastructure pressures, or not having adequate amounts of

urban zoned land for development.

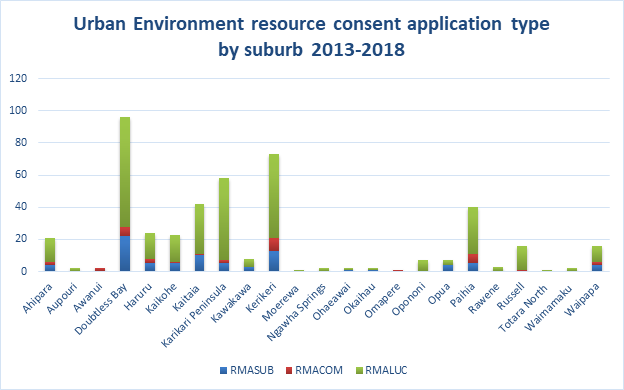

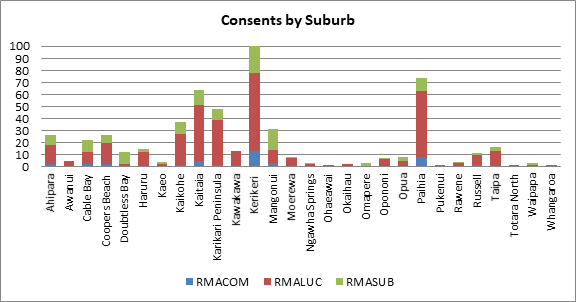

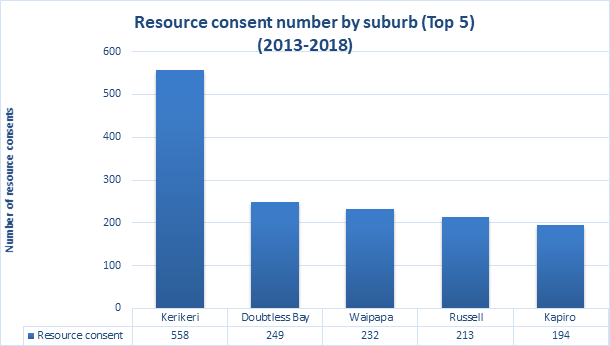

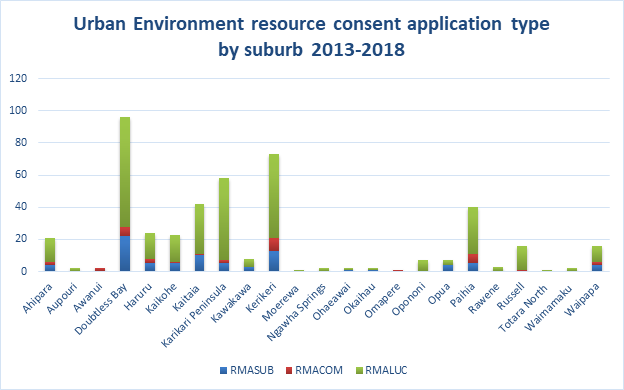

· A

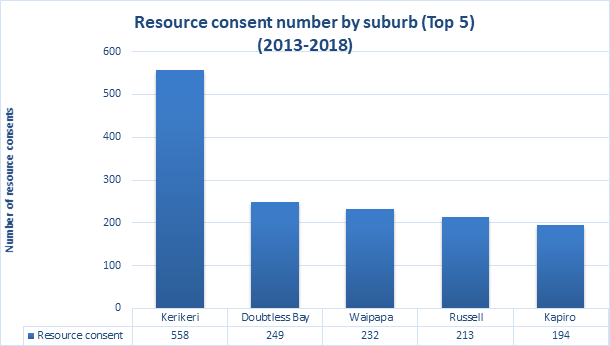

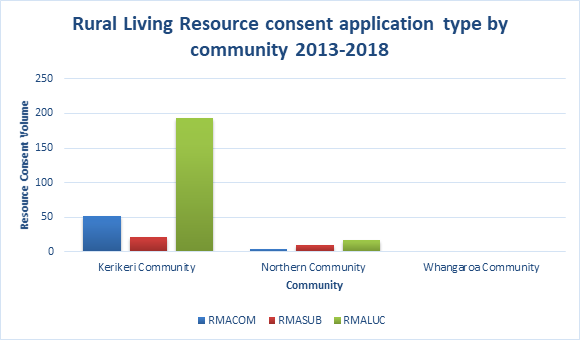

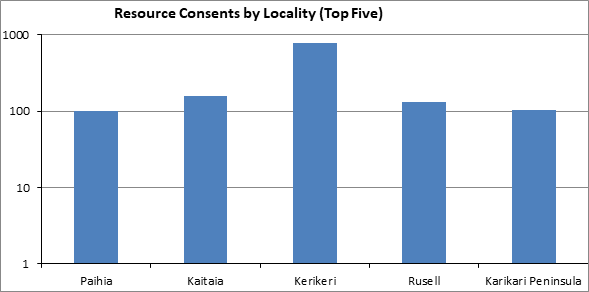

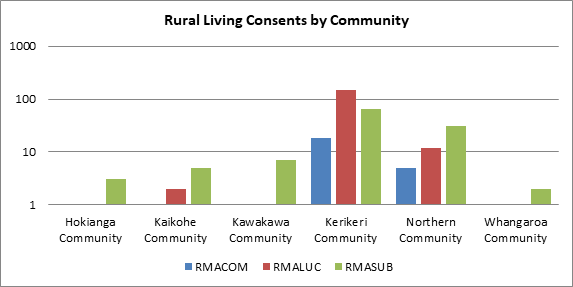

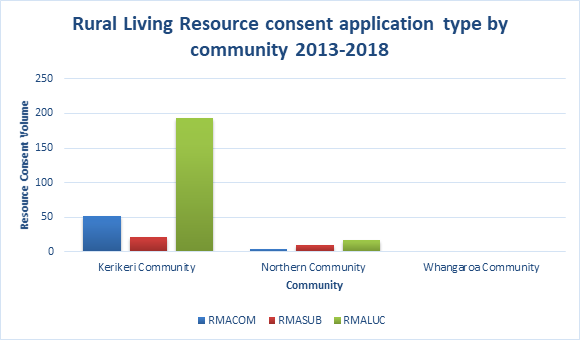

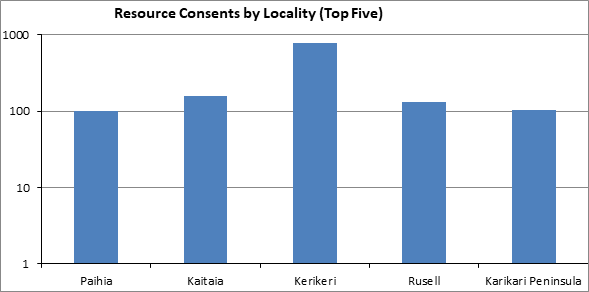

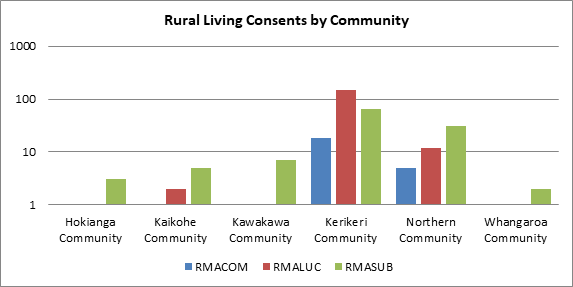

large portion of resource consents were granted in Kerikeri and Northern

communities over the 5 year reporting period. This is consistent with known

growth patterns in each of these areas. In particular, Kerikeri had the most

resource consents for any one place in the Far North.

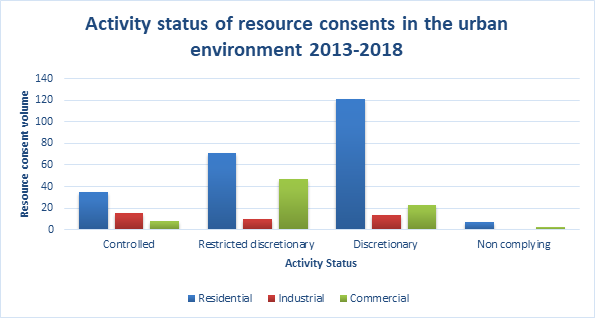

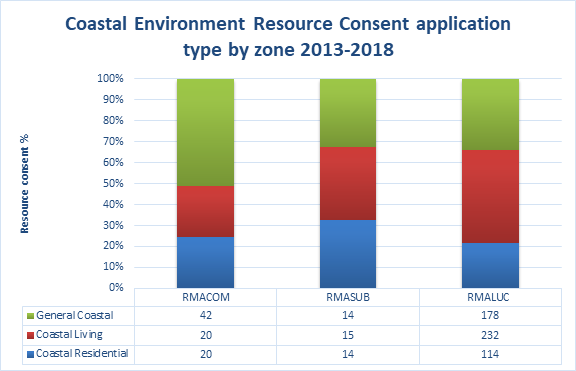

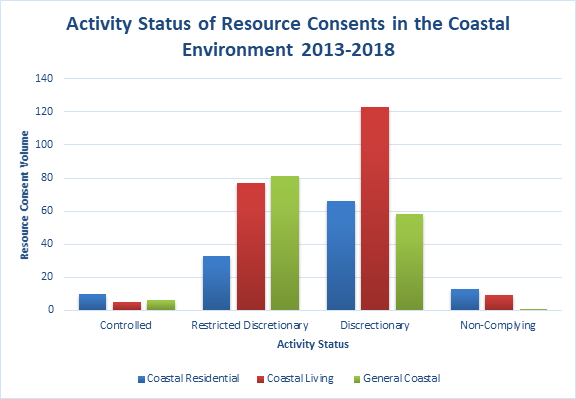

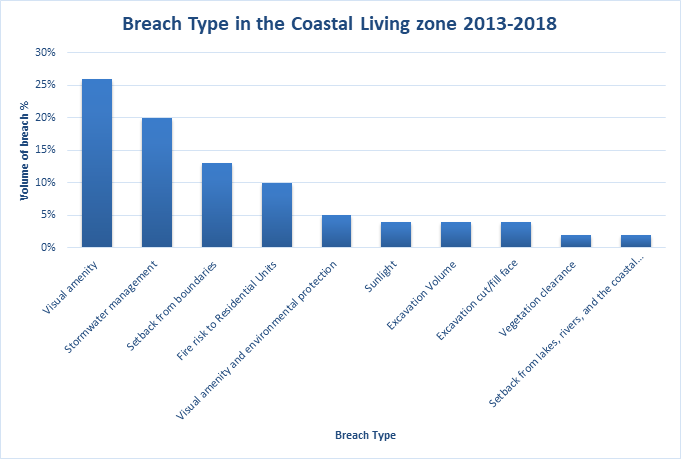

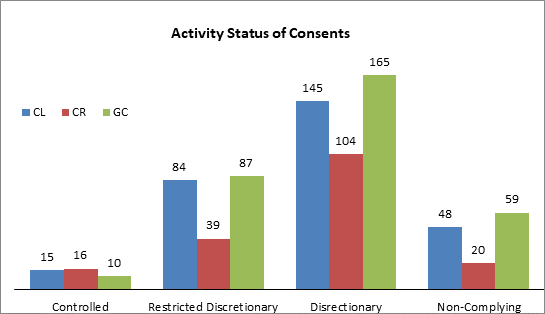

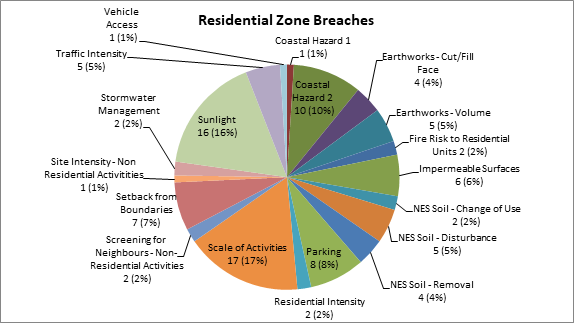

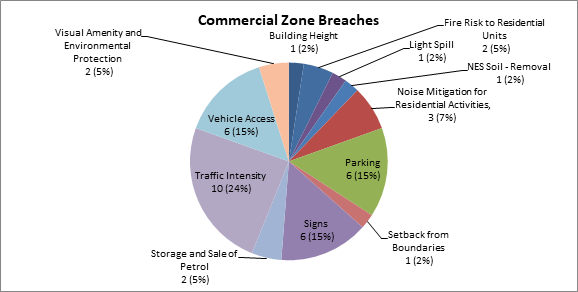

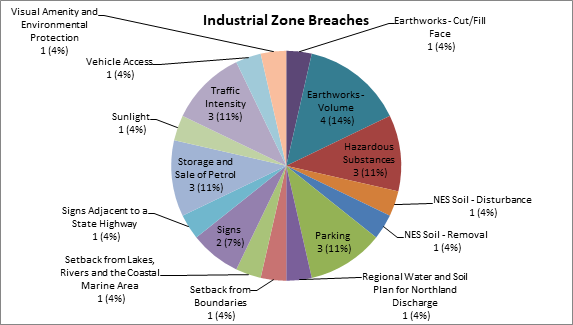

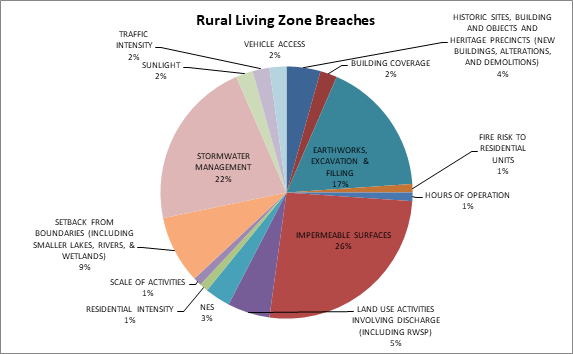

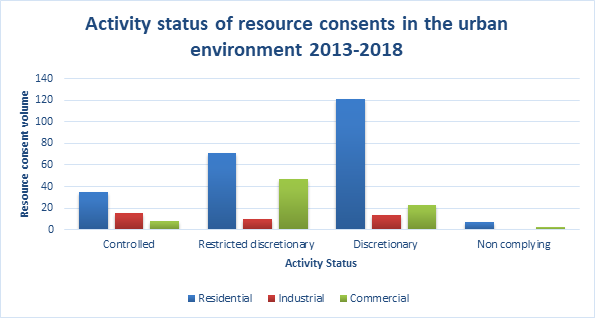

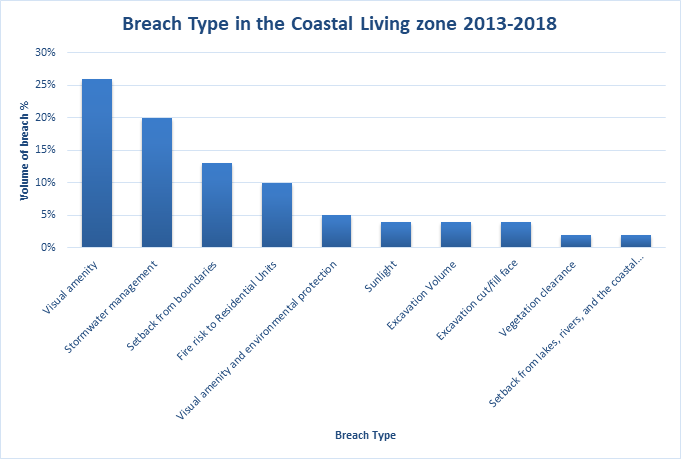

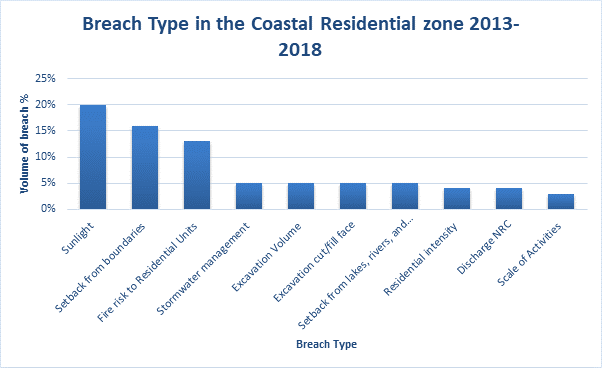

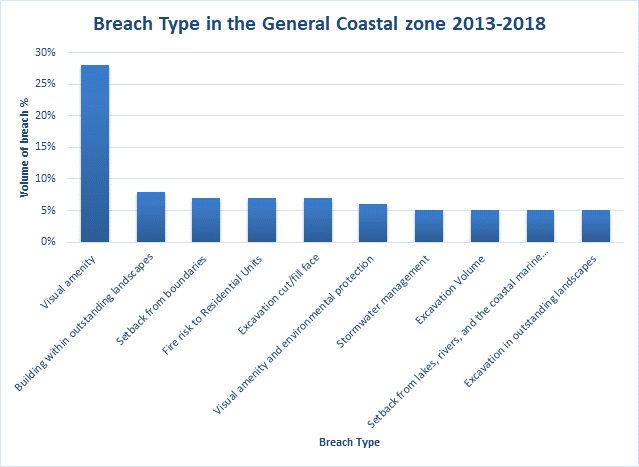

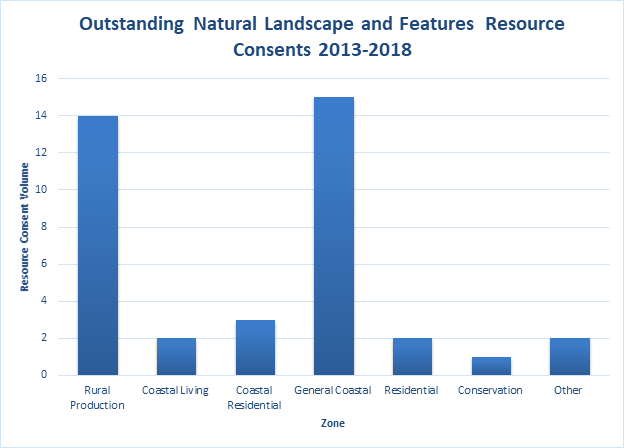

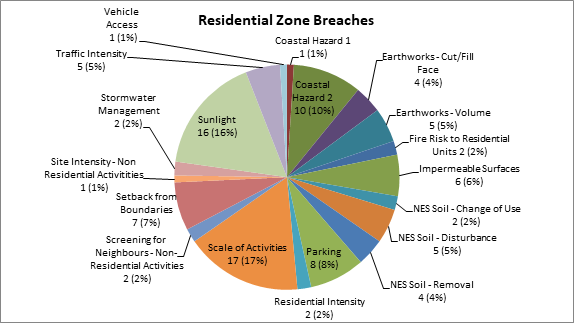

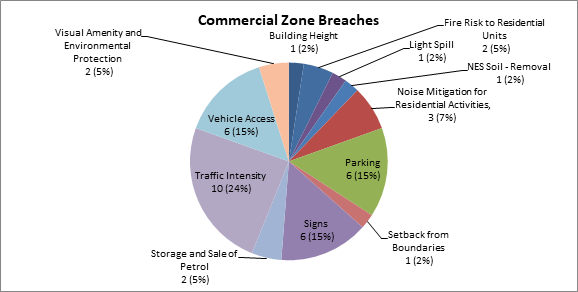

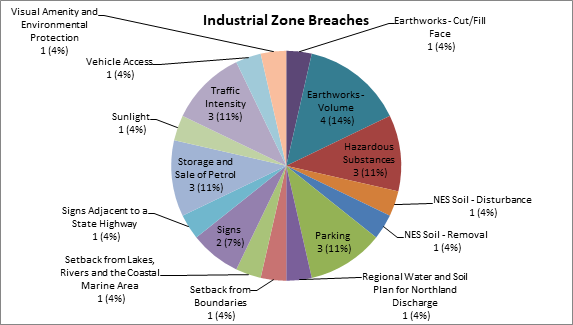

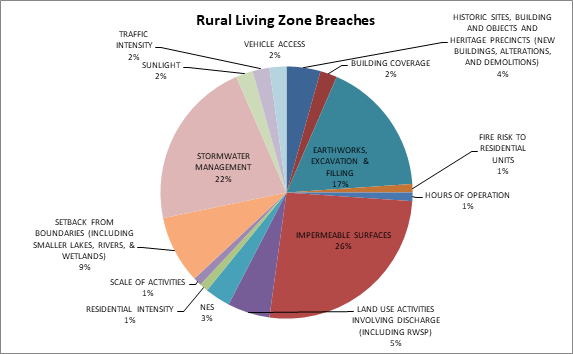

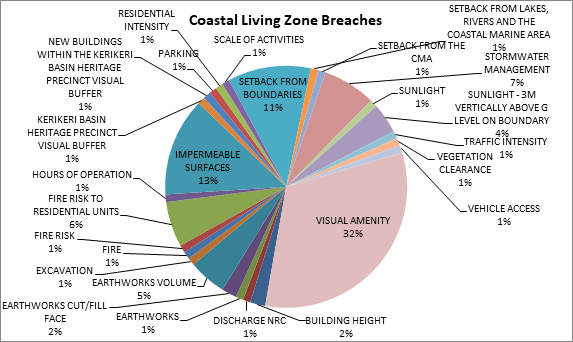

· Each

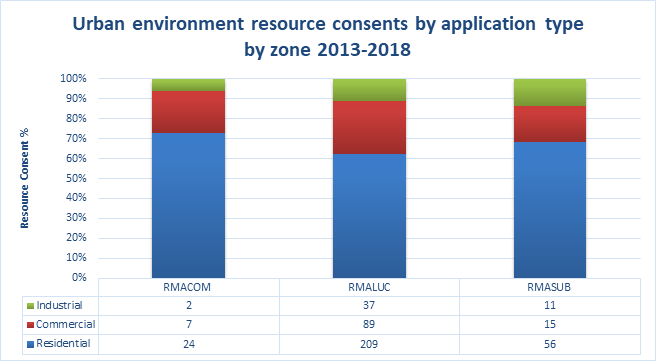

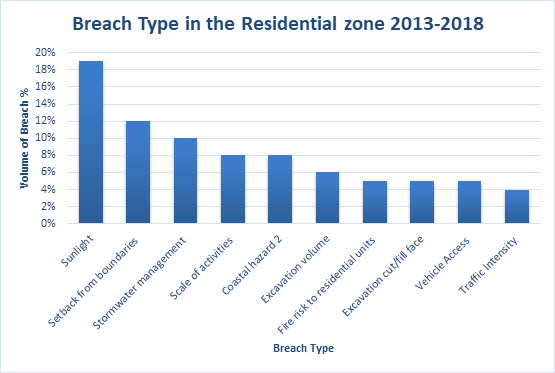

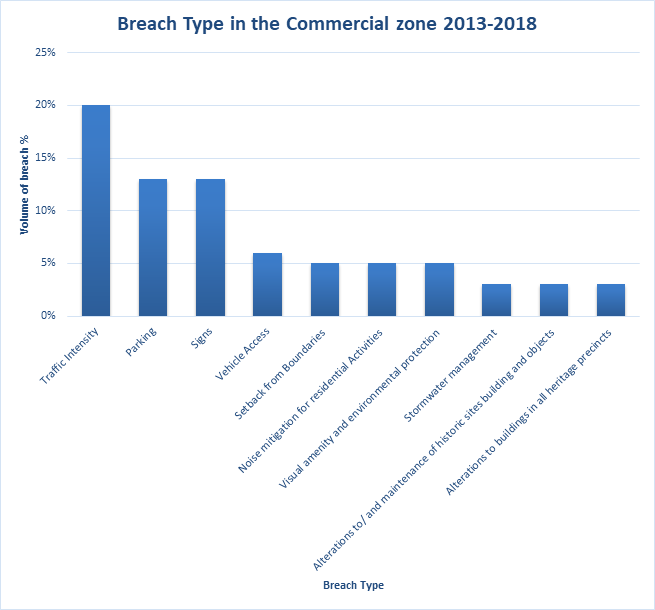

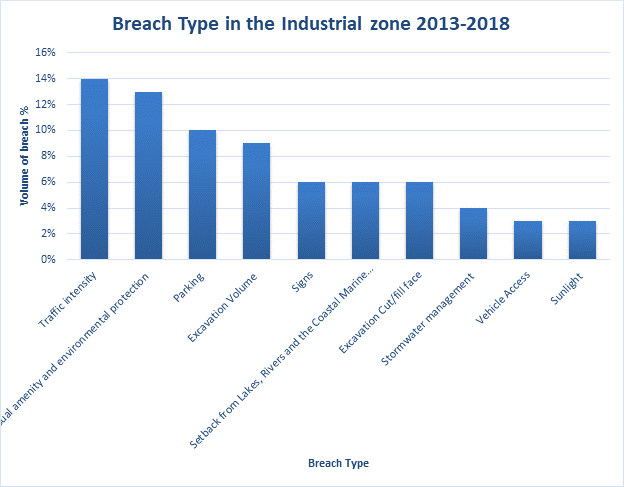

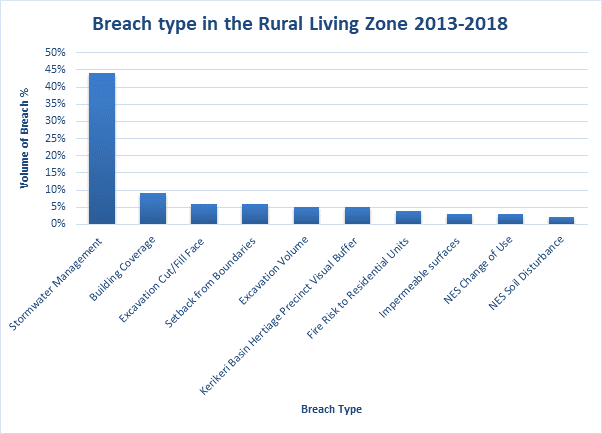

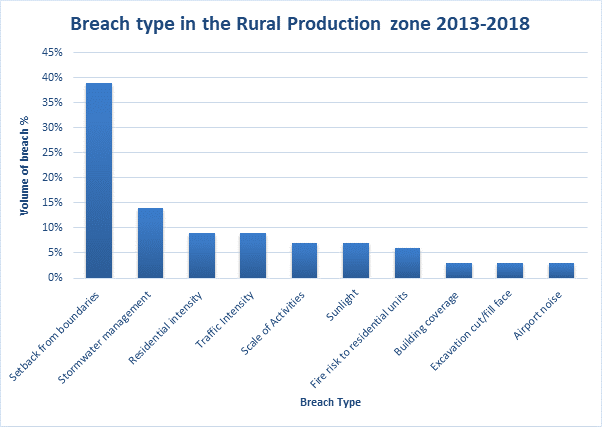

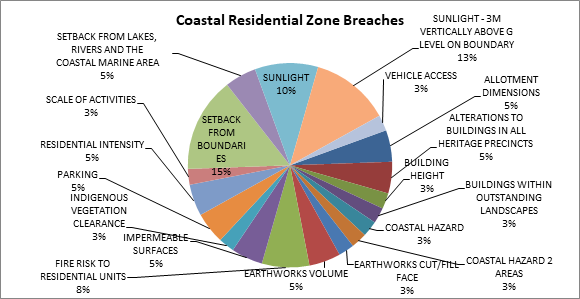

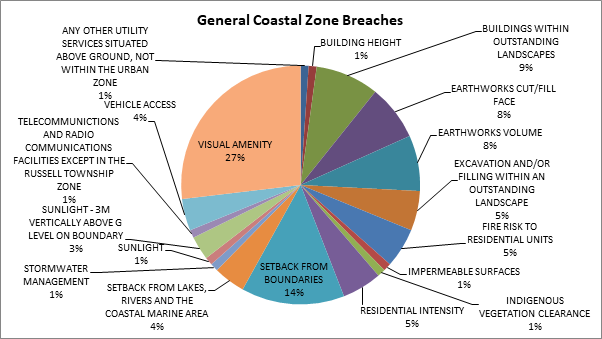

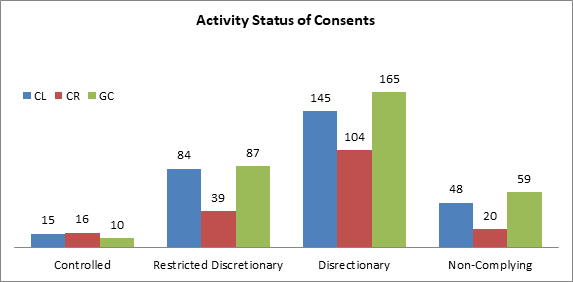

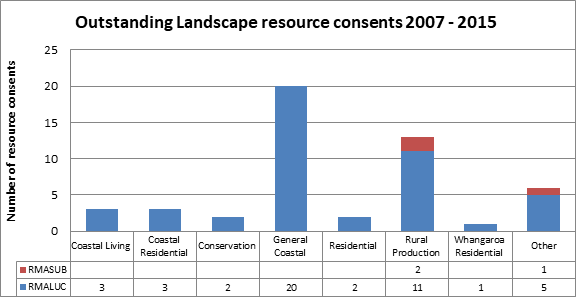

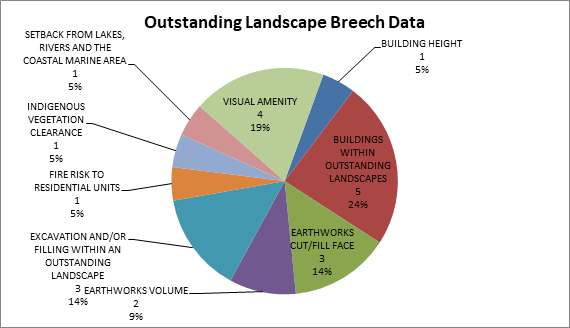

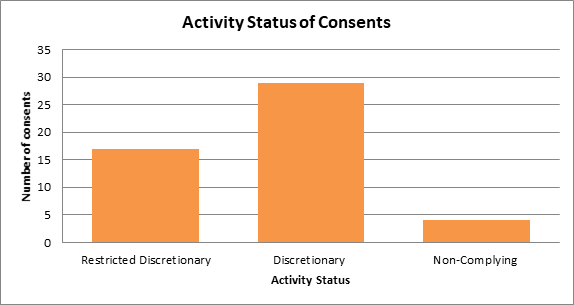

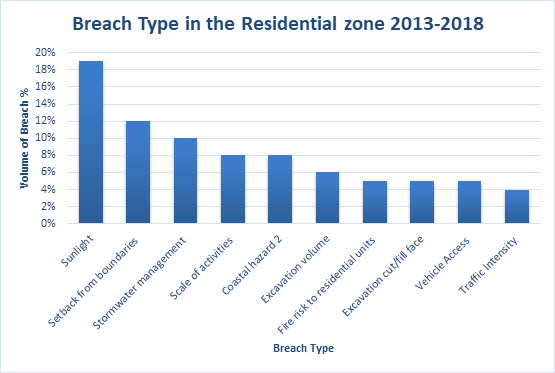

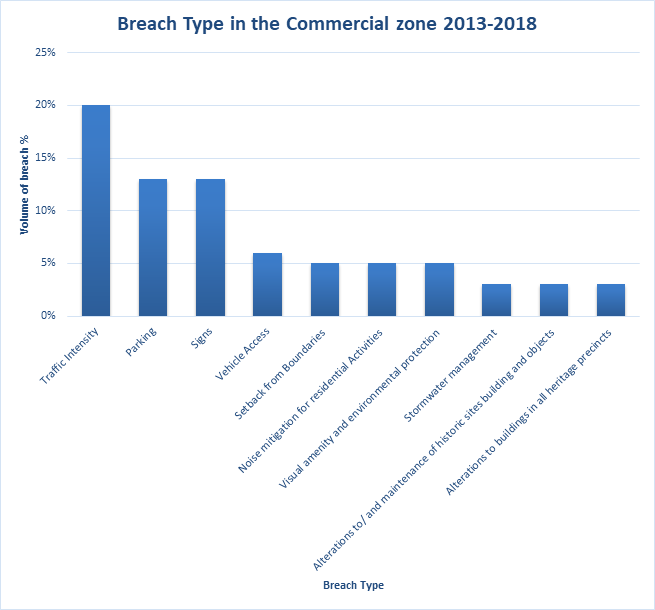

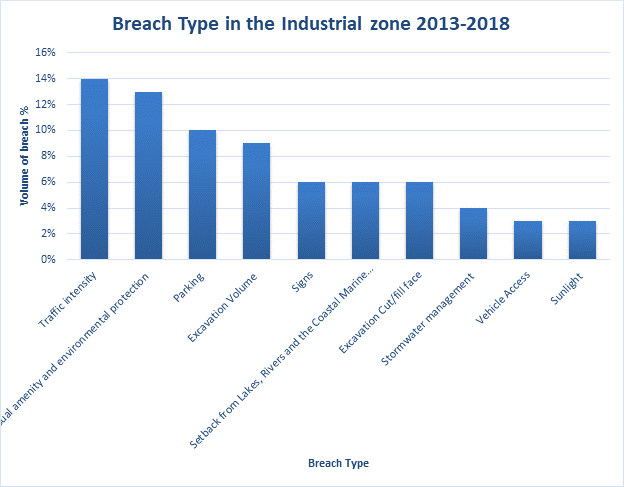

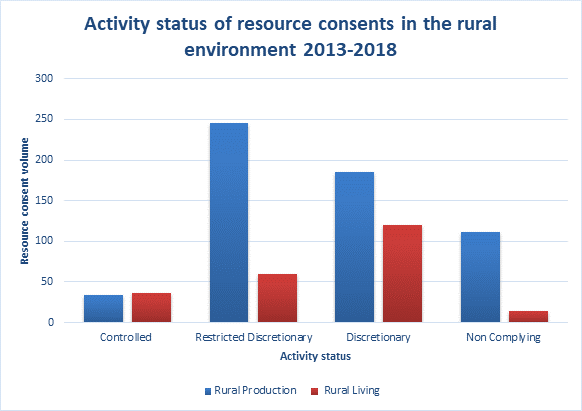

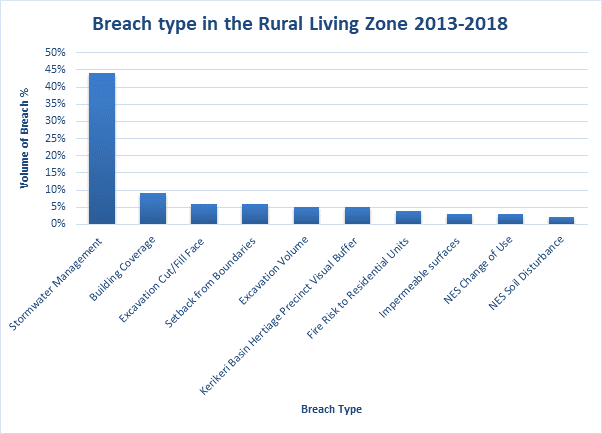

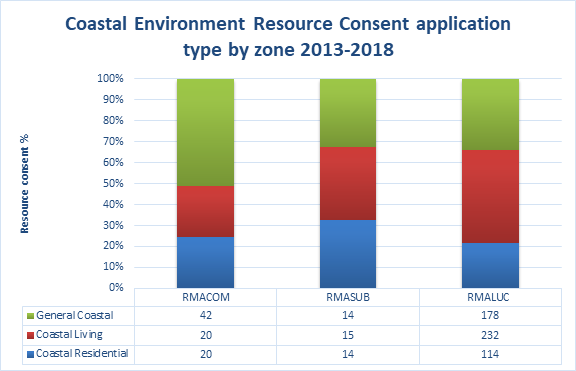

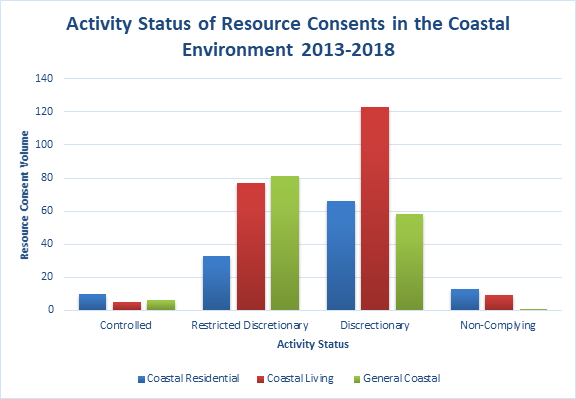

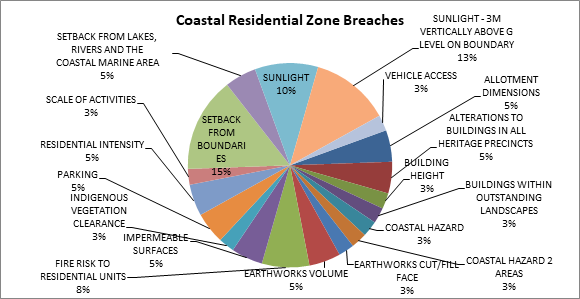

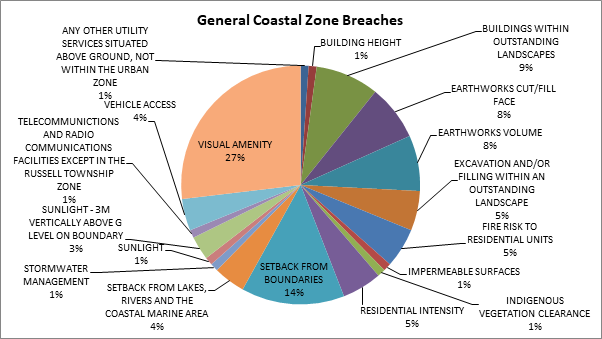

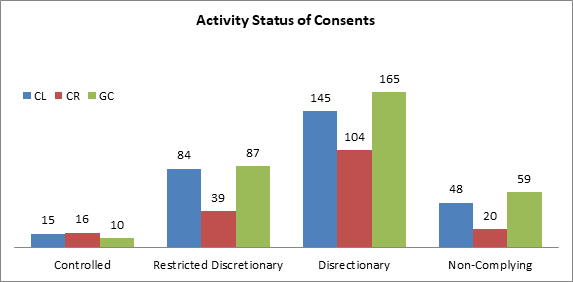

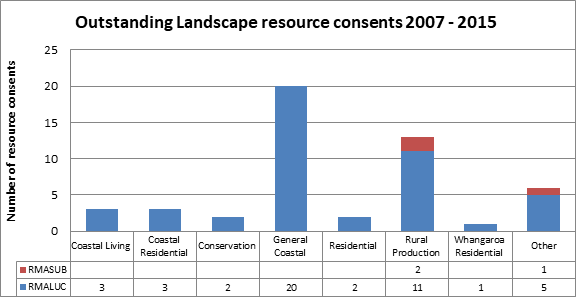

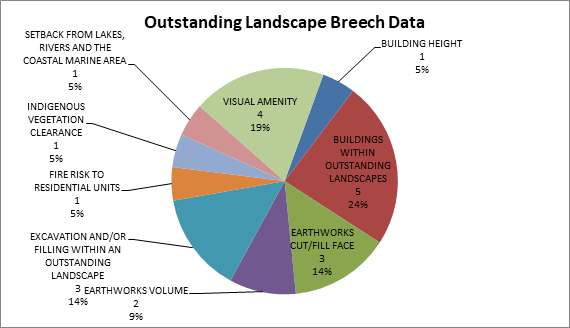

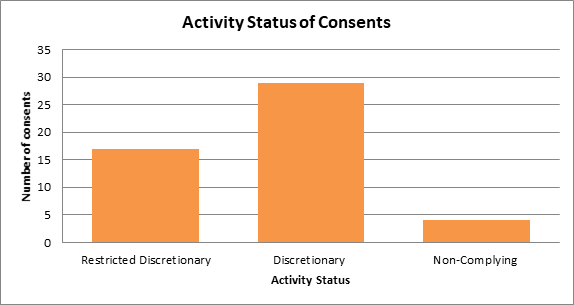

zone was analysed to give an indication of what types of consents were granted

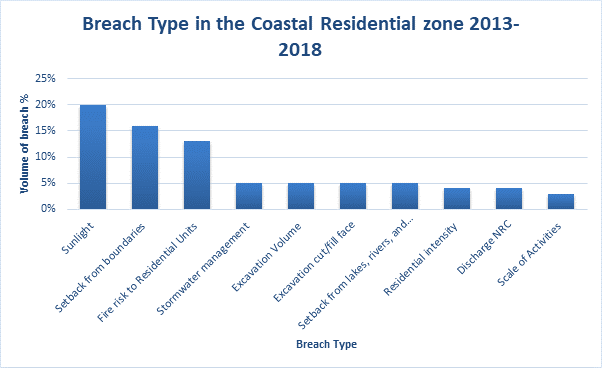

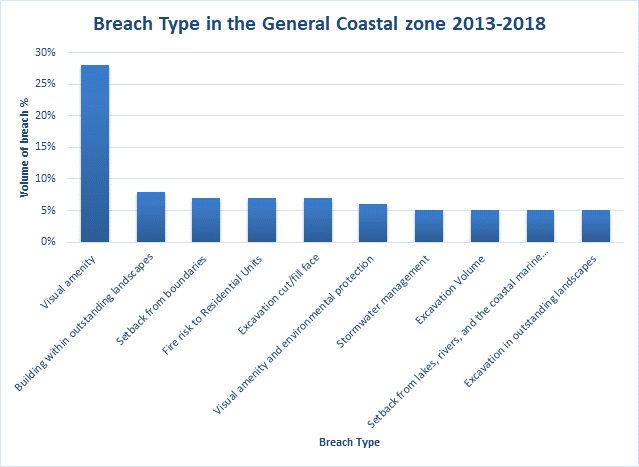

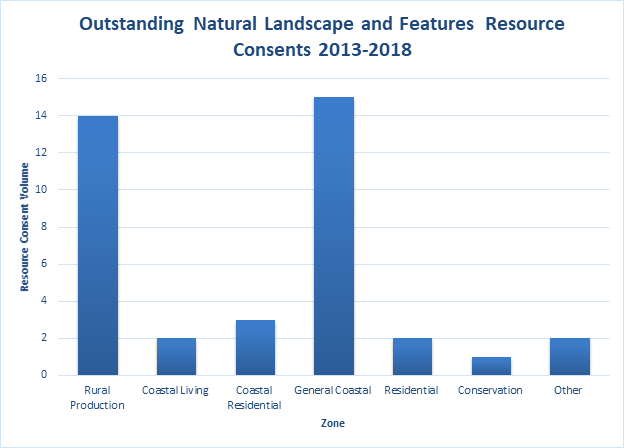

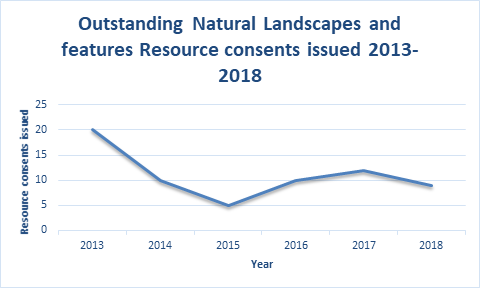

in these zones, including the main breaches for that zone. This information

gives us an idea of the most common consent types and will assist in the

District Plan review.

Discussion

and Next Steps

Under Section 35 of the

RMA, Council are required to produce a report on the efficiency and

effectiveness of the Plan, and to release this report to the public.

Previously, a comprehensive report was produced in 2015 which was taken to

Council at the time. The current Section 35 report will be made available to

the public, in order to ensure that they are able to participate in the RMA

process, and to ensure that our internal consenting processes are transparent.

Financial Implications and Budgetary Provision

There are no direct

financial implications as a result of the Section 35 report, however it is

anticipated that the report will be used as a tool in the current plan making

process, and may enable Council to review internal processes in order to create

efficiencies in both consenting and monitoring in the future.

Attachments

1. Section 35 Report

- A2873239 ⇩

|

Strategy and Policy Committee Meeting Agenda

|

30 July 2020

|

|

A

Review of the Efficiency and Effectiveness of the Far North District Plan

A

report prepared under Section 35 of the Resource Management Act (1991)

April 2020

|

Table

of Contents

Summary Report

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Legislative

changes

1.2.1 National

Direction

1.2.2 Local

Direction

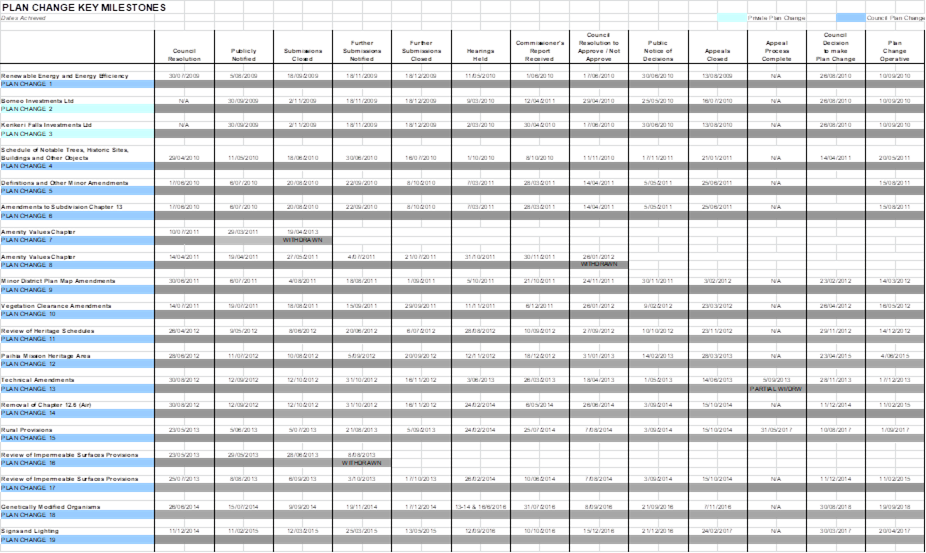

1.3 Post-operative

plan changes

1.4 Data

sources

2 District

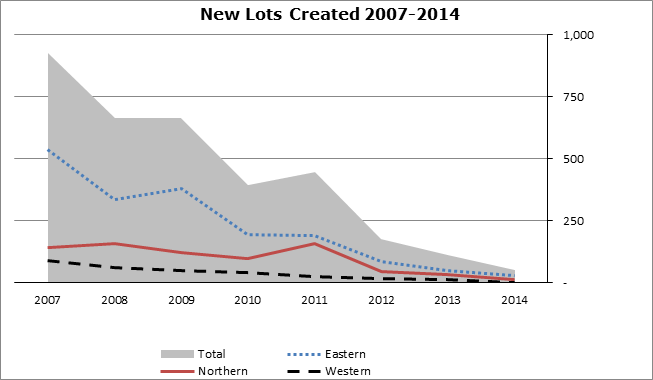

Wide Analysis

2.1 Development

trends

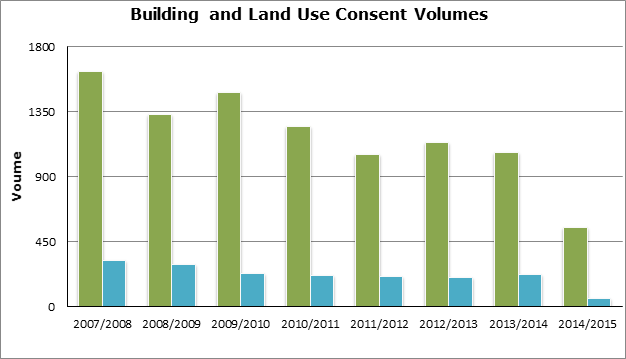

2.1.1 Comparison

between building consents and land use resource consents

2.1.2 Number

of resource consents granted

2.2 Resource

consent location analysis

2.3 Resource

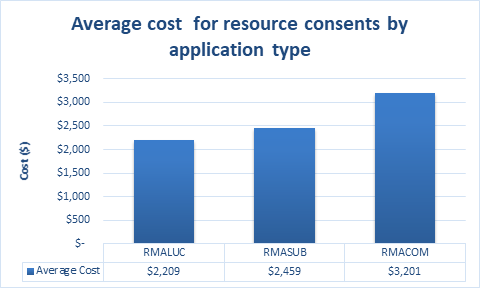

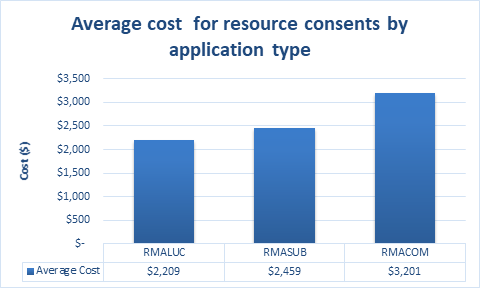

consent processing

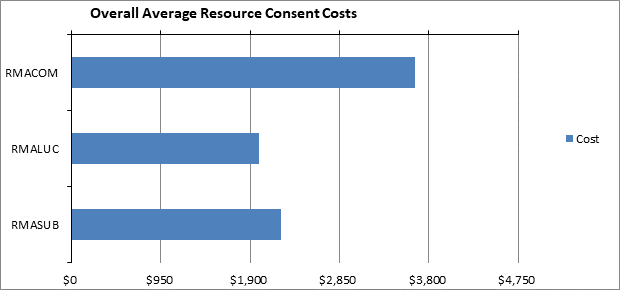

2.4 Resource

consent costs

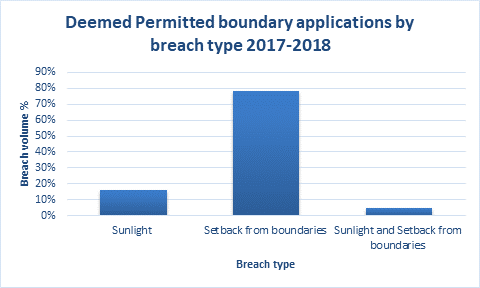

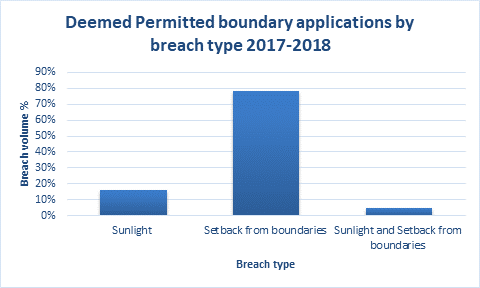

2.5 Deemed

permitted boundary consents

2.6 Designations

3 Environment

trends and analysis

3.1 Urban

environment

3.2 Rural

environment

3.3 Coastal

environment

4 District

wide reporting

4.1 Tangata

Whenua

4.2 Outstanding

natural landscapes and features

4.3 Indigenous

Flora and Fauna

5 Appendices

Appendix A - Effects Based Rule Thresholds

Appendix B – Key Dates, Plan Changes

Appendix C - Section 35 Report 2015

Summary Report

Councils are required to gather

information, undertake monitoring and keep records in order to effectively

carry out their functions under Section 35 of the Resource Management Act (RMA

1991). At least every 5 years, Council must prepare a report on the

effectiveness and efficiency of the rules, policies and other methods in its

plan, and make this report publicly available. Administration have

prepared the Section 35 report to assess and report on the effectiveness and

efficiency of the Operative District Plan in fulfilling the sustainable